The climate and ecological emergency (CEE) touches every corner of the globe, affecting the lives of each and every one of us. We are truly in this together. However, some of us are being hit harder, sooner. Climate breakdown affects populations differently depending on a number of geographical and socio-political factors. Those effects are also deeply rooted in historic and systemic inequalities which are reproduced and deepened further through the CEE, creating an extreme and vicious cycle.

Understanding Environmental and Climate Justice

It sounds like a mouthful, but let’s break down some of the terms in that first paragraph to make sure we’re all on the same page.

When social attitudes and political policies or practices interact, they can be labelled ‘socio-political factors’. One example is violence against women: this takes many forms and happens around the world because of differing negative social attitudes towards girls and women. It continues, in part, because laws either do not protect women from violence, or in some cases, punish them for it. We see the product of society’s attitude towards women’s safety reflected in political policies when we learn that in 1990, only four countries in the world had laws protecting women from violence.

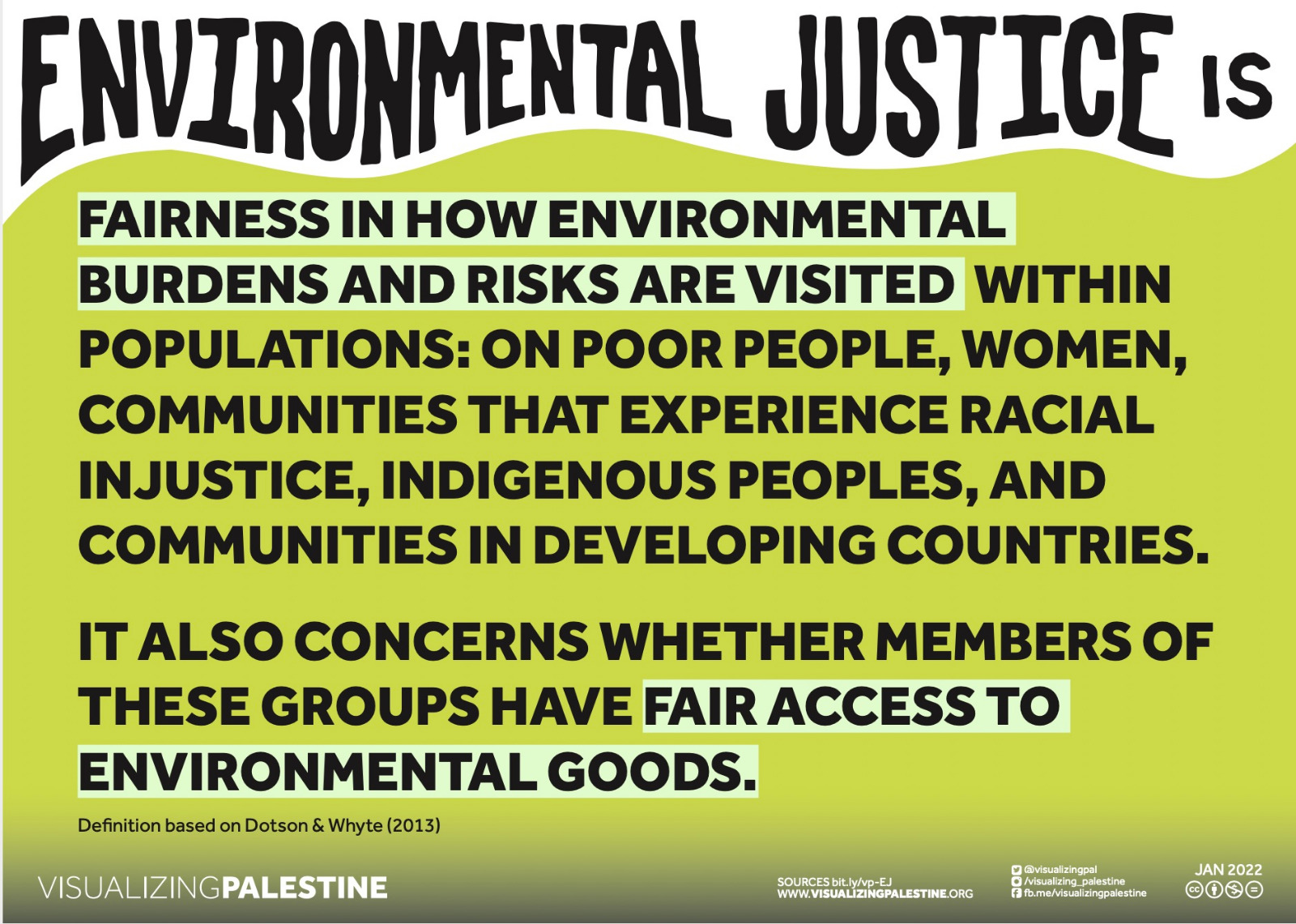

The second term, ‘systemic inequality’ (similar to ‘structural inequality’), refers to factors of inequality built into the social and political systems that shape our lives, such as healthcare access, food security, education, housing, and employment. These systems are often experienced differently based on race and/or economic status. Understanding that these structures underpin the lived experiences of all of us allows us to see events through a ‘justice lens.’ This can (and should) also be applied to the climate and ecological emergency, leading us to understand people’s experiences with the CEE as issues of climate or environmental justice.

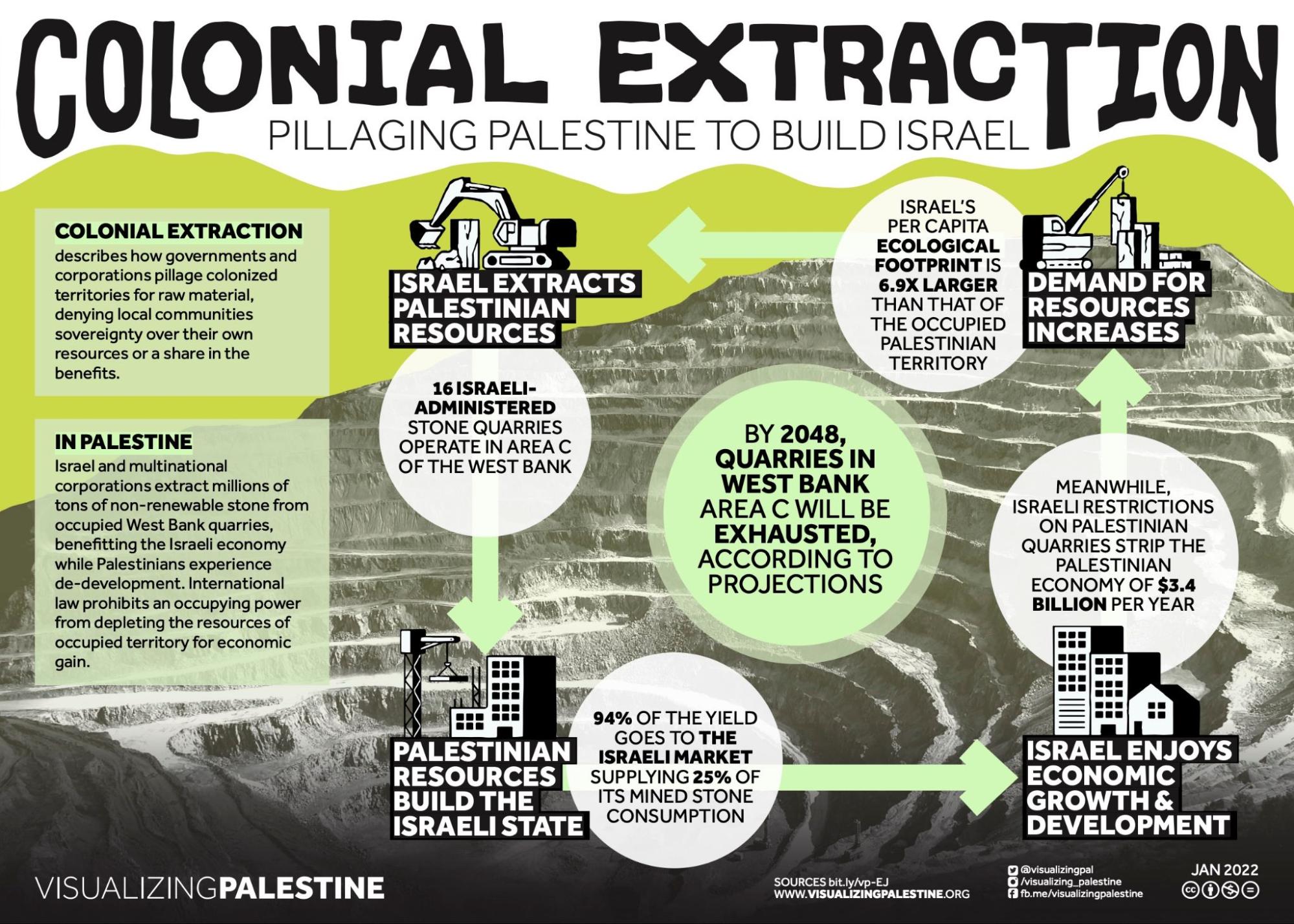

All visuals are Creative Commons licensed and are found at visualizingpalestine.org. The visuals in Arabic are at the end of the article.

The terms 'climate justice' and 'environmental justice' are used interchangeably, but 'environmental justice' came first, rooted in the experiences of marginalised black communities fighting back against their neighbourhoods being used as a dumping ground for toxic waste. 'Climate justice' is a newer term and relates to specific injustices linked to the rapidly accelerating climate crisis, but is also linked to the growth of climate-specific social movements in the 21st century and an understanding of climate injustices as truly transboundary, international issues that demand international solidarity.

Looking critically at different communities’ experiences with climate breakdown, local, regional, and global patterns emerge. Geographically, we can see a different impact on those living in the Global North versus people living in the Global South; and similarly, in both richer countries and poorer countries, we see different impacts being felt between those who are well off and the poor. We also see that there is a different experience between genders with climate breakdown, with women bearing a disproportionate burden, and that the CEE makes life even harder for people in conflict-afflicted areas.

Here, we zoom in on the climate and ecological emergency in Palestine, explained through infographics produced by Visualizing Palestine. We look at Palestinians’ experiences with colonization and climate breakdown, and see how they relate to experiences of other oppressed and marginalized peoples around the world.

Climate Vulnerability

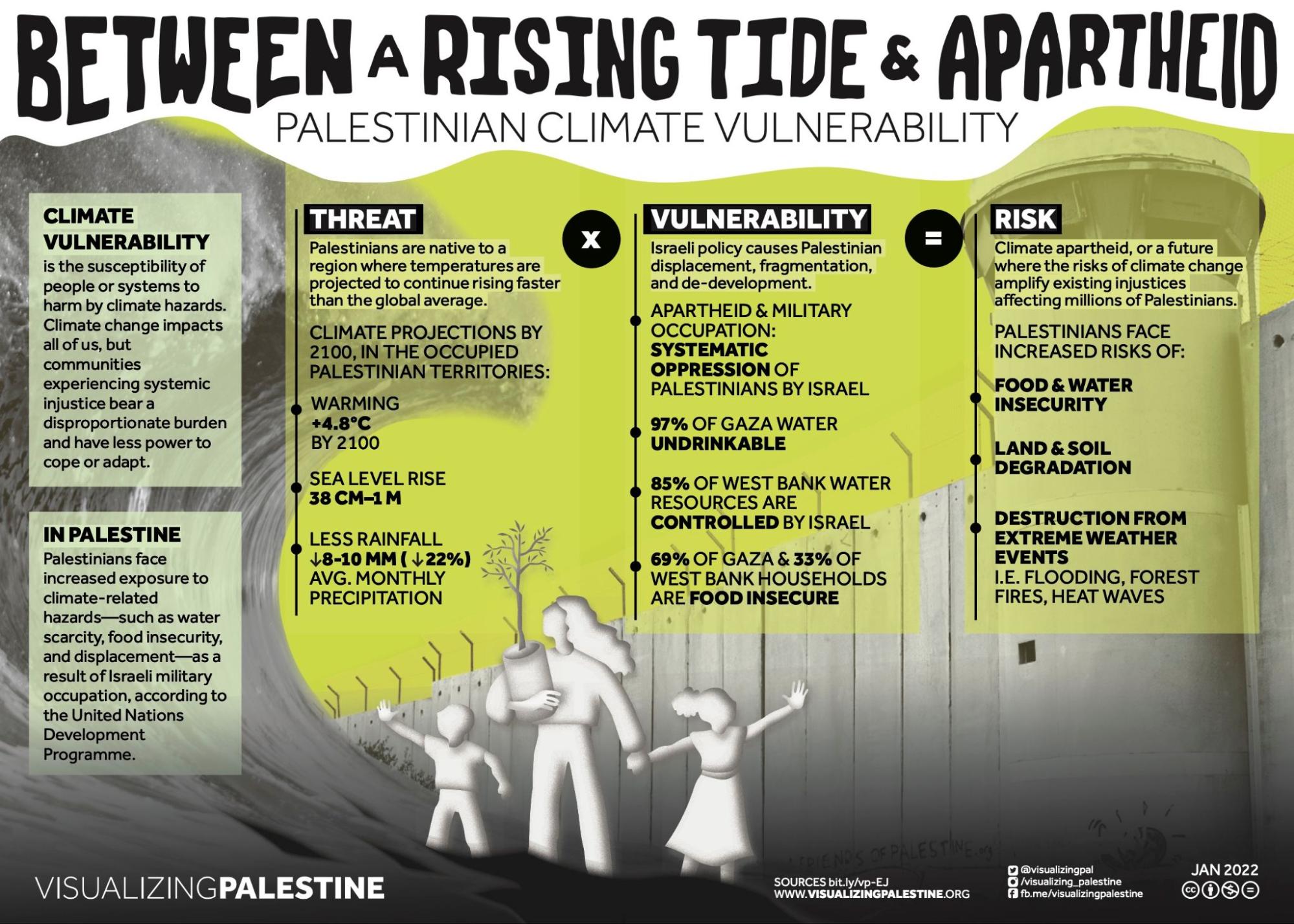

The state of Israel was established in 1948, ethnically cleansing, dispossessing, and displacing indigenous Palestinians from their homes. Since its inception, Israel’s rule over Palestinian life has morphed into a Kafkaesque, labirynthian web of control, geographically and socially fragmenting Palestinians from one another.

Enduring over 70 years of colonization and living under apartheid has made Palestinians a particularly vulnerable group, especially when contrasted with their colonizer, Israel. While they share the same landscape, Israelis’ and Palestinians’ experiences with political autonomy, climate adaptation, and control over resources are vastly unequal, leaving Palestinians’ hands tied with how successfully they can tackle climate breakdown.

Similarly, across the world, populations and communities who are marginalized due to age, gender, race, citizenship status, ethnicity, or economic ability may be more climate vulnerable than others. In Europe, we see this in the high number of elderly people who die during heat waves. In the US, communities of color experience greater climate vulnerability due to systemic inequalities. We see Black Americans’ vulnerability laid bare in the face of toxic wildfire smoke, and the disproportionate devastation they experienced during Hurricane Katrina, which was then reinforced by government ‘rebuilding’ programs after the storm. These experiences reinforce the disadvantages already faced by these communities. Writing about Katrina and subsequent storms, Professor Andy Horowitz reminds us:

The wind isn’t racist, and the rain doesn’t target the poor. But when hurricanes strike and cities flood, people who were already disadvantaged tend to suffer the most. That’s because the wind and rain alone do not define the shape of our modern disasters[...] There have been calls not to ‘politicize’ the recent storms […b]ut rather than closing our eyes to the political decisions that shape our communities, we should open them wide. A disaster without politics would be an event without a history, a catastrophe without a cause.

Let’s be clear: the climate and ecological emergency is a disaster, one with unique, dynamic events (such as Hurricane Katrina) occurring within it. Pacific Island nations are particularly vulnerable to the climate and ecological emergency, with many threatened to be underwater with rising ocean waters. Around the world, the climate crisis is already displacing millions, forcing them to leave their homes and seek refuge elsewhere. We, not the rain, have shaped this disaster and people’s vulnerability to it.

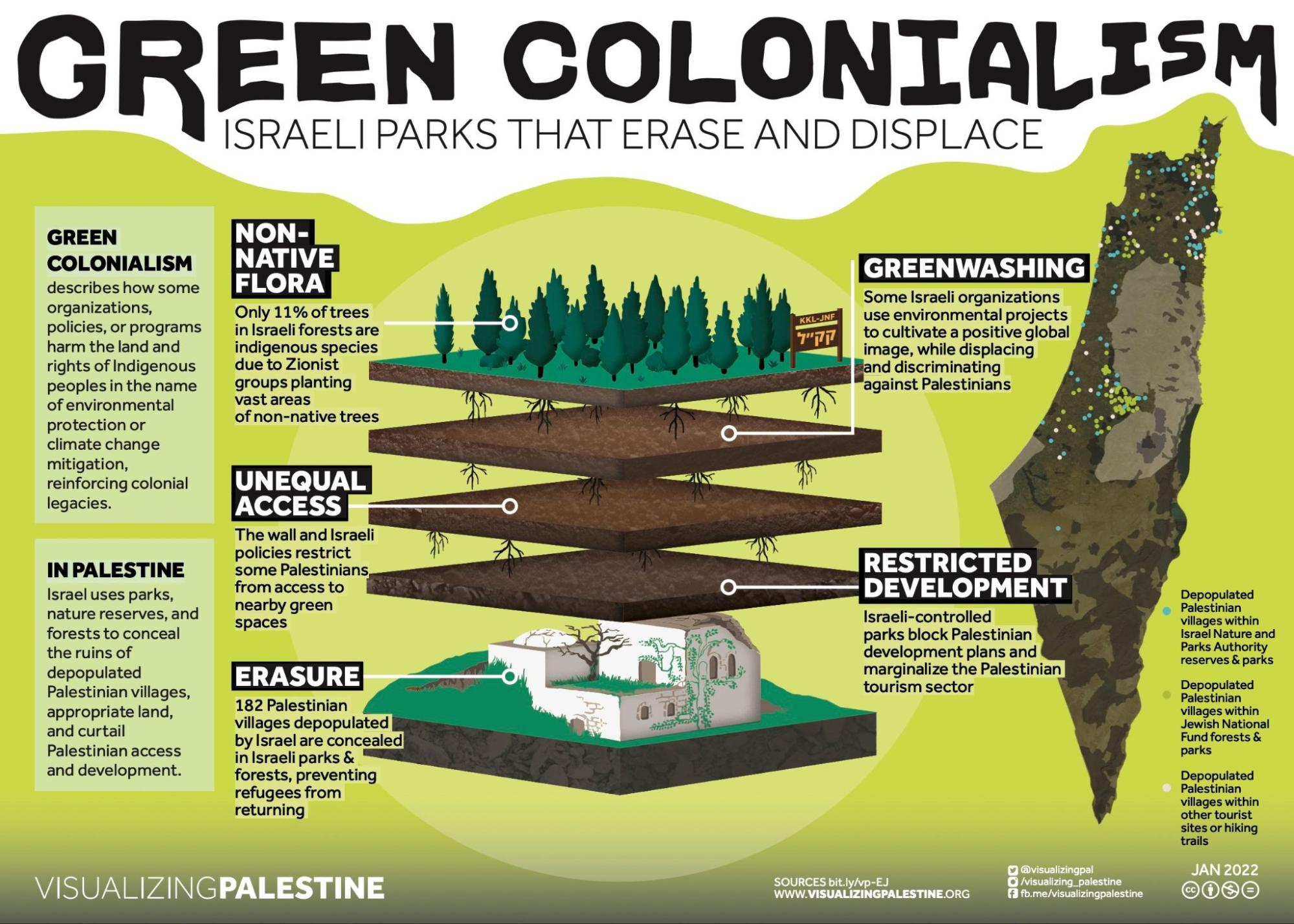

Green Colonialism

The term ‘green colonialism’ refers to the greening or conservation of land at the expense of indigenous populations. This might take the form of building a national park on indigenous land or restricting access to green spaces for conservation efforts, and is deeply rooted in the ‘othering’ of poor communities, indigenous peoples, and people of color. This enables those in power (whether national governments or colonizing powers) to disregard the rights of these marginalized communities, because, as Naomi Klein points out, “... rights are meaningless when the land is desecrated.” Othering allows ‘national sacrifice areas’, and, in turn, dictates the people whose land and lives will be sacrificed.

In Palestine, green colonialism has been central to Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestinian society, cheerily embodied in the catchy slogan that it will ‘make the desert bloom,’ while nefariously masking land seizures and displacements of Palestinian communities. Among other practices, Zionist organizations heralded themselves as ecological experts by covering Palestine with European pine trees, replacing indigenous trees and covering their destruction of Palestinian villages. This made the land more familiar and ‘homelike’ for Jewish European settlers and made it more difficult for Palestinian refugees to return. Digging its heels into the erasure of Palestinian life and charging on with its plan of a European vista, Israel sidelined indigenous Palestinian knowledge and banned black goats in 1950, a move which has accelerated the wildfires in Israel today.

Shrouded in promises of ‘carbon off-setting,’ ‘making the desert bloom,’ and conservation, green colonization is perhaps one of the most hidden symptoms of both colonialism and climate injustice. Carbon off-setting may be an unfortunate necessity in the context of continually rising emissions levels, yet it often comes at the expense of Indigenous communities’ access to land. While land conservation is critical to the restoration of our living earth, it must be done in partnership with (or better yet, led by) Indigenous communities, rather than severing their relationship with the land, as was perpetrated against Native Americans in what is now Yellowstone National Park, or as is happening now with the Maasai tribe in Tanzania.

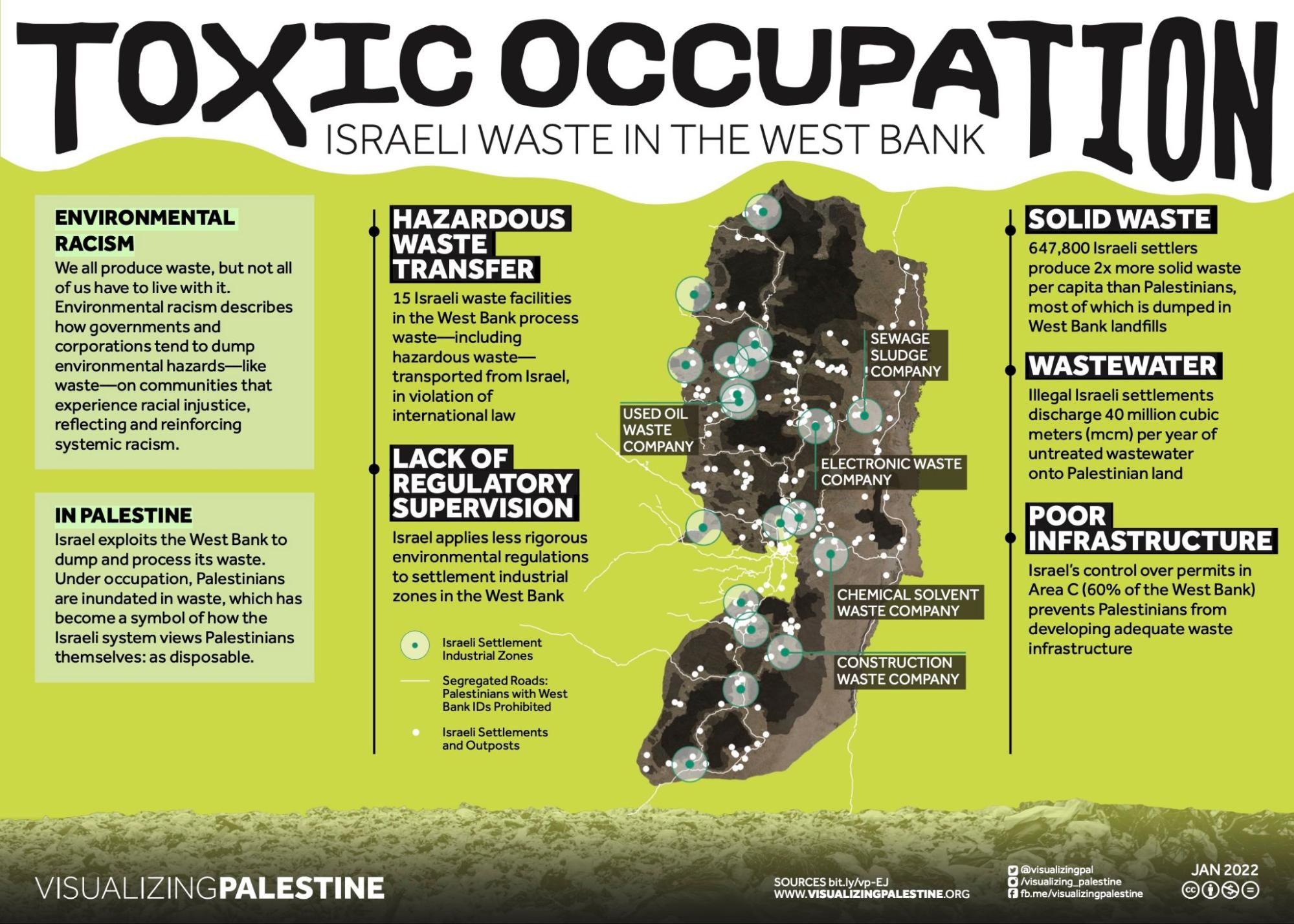

Environmental Racism

Government and corporate powers often take liberties dumping their toxic waste into poor or minority communities. The comparison of who has clean water and who doesn’t is sometimes as stark as which side of the line you live on. In Orosi, California, it’s the east side of town whose water is poisoned by agricultural waste runoff, and children have to bathe with their mouths closed so they don’t accidentally swallow the water. East Orosi’s contamination is consistent with the fact that “water systems serving Latino communities have twice as many strikes against them for drinking water violations as the national average.” In poor areas such as Griswold, Iowa, there’s no budget for cleaning up the water, similarly poisoned by agricultural runoff because, as one city councilor bluntly states, “We have many more needs than we have money.”

The national rich-poor divide is mirrored between countries in the Global North and those of the Global South. In the 1980s and 1990s, European companies dumped industrial toxins on the Somali coastline, a move belying how completely inconsequential they viewed Somali lives to be. Today, Kenya (like many countries in the Global South) faces a literal mountain of a problem with the Global North dumping its plastic and other waste there. Again, this can only happen in communities that are viewed as ‘lesser than’ or ‘ok to be sacrificed’ because, as one North Carolinian activist bluntly acknowledged, “they chose us because we were rural and poor and thought we couldn’t fight it.”

These predatory practices target weaker communities. Israel routinely dumps its waste in occupied Palestine, where Palestinians desperate for a means of income burn plastic waste creating carcinogenic emissions, contributing to the increasing levels of cancer among Palestinians. Israel’s decades old blockade of the Gaza Strip—coupled with its repeated bombings of its electricity plants—has left only three percent of water drinkable, creating an unimaginable health crisis for Palestinians living in an unlivable place. In a colonial expression of supreme indifference, Israel then routinely denies Palestinians permits to enter Israel to treat their illnesses. Again we are reminded just how ‘disposable’ and ‘sacrificial’ some lives are seen to be.

Colonial Extraction

Being the insatiable leviathan it is, colonial forces target natural resources for their own capital gain, extracting them with reckless disregard for either the earth’s regeneration or Indigenous benefit. Here we should pause to be clear: humans have always used the earth’s resources, however ‘colonial extractivism’ brings with it capitalism’s ethos of domination over nature and indifference to human wellbeing. Its ‘winner takes all’ mantra sets it apart from a more balanced, regenerative approach to use of the earth’s resources.

Colonial extraction is harmful in several ways. Let’s take the example of Congo, first snatched by King Leopold of Belgium in 1885. The Belgian king quickly discovered rubber trees’ money-making potential and set his colonial soldiers to work overseeing the collection of rubber and wreaking an unimaginable brutality upon the Congolese human beings he had reduced to cogs in his resource-extracting-machine. He not only cut them out of any profit he was making, he cut them up as well. But he was making money and Brussels was beautifying itself with this inundation of wealth, and others wanted to get in on the rubber boom. Rubber (and Indigenous people) were exploited in Peru and, once that tap dried up, Europeans cleared large swathes of native trees in South East Asia, replacing them with rubber producing trees to keep up with European and American demand for tires and the burgeoning automobile industry.

And you’ll never guess what natural resource was next up on the list for mass extraction at the expense of Indigenous and local communities…but we’ll leave oil alone, for now…

The devastating human and environmental cost of colonial extractivism still reverberates and continues today. Colonialism actively de-developed and impoverished resource-rich areas around the world, a legacy with which they are still grappling. This destructive extraction is also carried out by governments and corporations who plunder resources from poorer areas within their own nations, without then reinvesting profits into those communities. This has been the story of Appalachia, one of the poorest areas in North America which was pillaged for coal. Like Appalachians, Congolese, and Indigenous communities in Europe’s Asian colonies, Palestinians also watch their natural resources being exploited for someone else’s profit.

Together, Forward in Justice

Is your head spinning? Does your heart hurt a bit and do you feel a slight knot in your stomach? Me too. And I’ve only written about it, I haven’t directly experienced any of this. Rather than retreat into a cloak of sadness or be paralyzed by guilt and the breadth of injustices in the world, we must rise up in solidarity and action.

The infographics above give us a glimpse into the layered history and realities of Israel’s colonization of Palestinian land and lives. They help us understand that environmental degredation and the resulting vulnerability of Palestinian communities is one of the pillars of Israel’s colonization of Palestine, and colonialism at large. Once we approach it in this frame of mind, we see that the CEE is an issue of justice. This is where solidarity begins.

Connect the Dots

The world is often presented superficially and with the privilege of distance, meaning that things just ‘are as they are.’ Poverty just exists. Bad health outcomes just happen. Food shortages just appear. But these phenomena do not exist in a vacuum; they are the product of history (which we know is often written by the ‘winner’ and leaves out all his dirty work) and the systems we have created and perpetuate. Remember the quote from the beginning of this article? “A disaster without politics would be an event without a history, a catastrophe without a cause.” We must understand history to know where we are going, and just as we have created destructive, toxic systems, we can rediscover, reimagine, and reinstate regenerative systems that grow a more just and equal world. The climate crisis is not simply a matter of science, it is a matter of justice.

Be an Ally

We are all in this together. We must stand shoulder to shoulder against the climate and ecological emergency, but also the injustice it brings with it. By understanding that our outcomes are intertwined and that we have an obligation to one another—both as human beings and in redressing historic wrongs—we may become allies to other communities around us. This means providing space for Indigenous and marginalized narratives. This means respectfully listening to their experiences as truths and not as personal attacks (which they are not). This means making sure Indigenous peoples’ knowledge is recognized, respected, and their expertise sought. This means questioning mainstream narratives that encourage ‘othering’ and making an active effort to read and seek out voices from the Global South and other marginalized communities. This means raising your voice and navigating conversations about the CEE towards an angle of justice.

Demand Justice

Make sure when you are demanding solutions to the climate and ecological emergency that they incorporate elements of justice. This means investing in communities who suffer disproportionate health hazards as a result of the crisis, whose greenspaces have been dismembered from them, whose natural resources are privatized with social and material benefits diverted away from them. This means demanding a restructuring of systems built to benefit some rather than all. This means demanding a dismantling of occupation, colonization, and militarization in Palestine—and elsewhere in the world. This means when you write a letter to, or take direct action against Shell to stop their growing extraction of fossil fuels for example, also demand restitution to the Indigenous communities they have dispossessed in the process, and about their plans for earth regeneration.

I know this sounds like a lot. It is. We have big messes to clean up, but we can do it.

We must remove ourselves from powers that support fossil fuels and indirectly sideline Indigenous rights. We must alter our lives away from fossil fuels and gas which bankroll militarization and war, as we are currently witnessing in Ukraine. We must hear and amplify calls for climate justice. The good news is that there are increasingly accessible options to live away from oil and gas, and marginalized voices are (finally, sometimes) being permitted entrance into the mainstream. None of us can do it alone, which is why we must tell the whole truth, come together, and act now.

Visuals in Arabic