Over the last thirty years, our relationship with our clothes has drastically changed. Our shopping habits are transformed and our wardrobes expanded. Where once we shopped with the seasons, it’s now normal to bag a weekly bargain with just the spare change in your pocket.

Yet while our bursting wardrobes may make us feel more 'complete' for a little while, it’s the environment which is bearing the devastating cost. The personal wardrobe has become intensely political, and it’s time we all got informed.

What is Fast Fashion?

Source: Unsplash

The Google searches which return the most hits for fast fashion all describe it in the context of three key qualities: i) Speed of production ii) Low prices and iii) Immense profits for the consumer-facing companies involved.

The Wikipedia entry, for example, goes as follows:

Fast fashion is a term used to describe a highly profitable business model based on replicating catwalk trends and high-fashion designs, and mass-producing them at low cost.

Wikipedia, January 2021

True. Fast fashion is indeed the rapid production of apparel which copies runway fashion trends. Garments are made for retailers at the lowest possible cost and then sold in vast quantities online and in high streets across the world. So far, so informative.

However, whilst these definitions are correct, they are also incomplete. All lack a fourth element, specifically, the element of exploitation. Retailers try hard to hide it, and many of us try equally as hard to ignore it. But when clothes are produced quickly and cheaply, they are also produced exploitatively.

"Why?" "How?" And "Can I still love clothes and skip the exploitation?" I hear you say. Well, for all you denim devotees, flare fanatics and lycra lovers, this is the blog for you.

What is Wrong With Fast Fashion?

The Human Cost: Exploitation and Death

The site of The Rana Plaza Building, 2013. Source: nyusternbhr, Flickr

Broadly speaking, we can use two big economic leaps to explain fast fashion’s path to power - The Industrial Revolution, and the later global push to neoliberalism.

In the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution saw textile machinery displace garment production from the household into textile mills and factories. In the UK, large numbers of poor women, men and children became the labour force behind a growing ‘ready-made clothes’ industry. By ‘sweating’ labour, factory owners paid them incredibly low wages, enforced mandatory overtime and maintained abysmal working conditions. All the while, the raw materials needed for this transformation in the productive process were 'outsourced' to the colonies, where slavery ensured cheap, unceasing labour.

Jumping forward two hundred years and we find ourselves in the midst of the increasingly globalised, neoliberal nineties. This brought on a rapidly changing system of worldwide clothes production. Acting on rising customer demands and new free trade agreements, western brands began to shift production overseas. They hired manufacturers, who in turn hired contractors, who hired subcontractors, who hired garment workers in the Global South. Large production bases for western brands were formed in countries with cheap labour and few regulations, and this lengthy 'commodity chain' means less transparency so big name brands can get away with murder, sometimes literally.

As this outsourcing continues today, our clothes workers are locked into a miserable race to the bottom. Factories throughout SouthEast Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia still compete to win subcontracts from western retailers. The vast majority (approximately 80%) of world’s garment workers are women, and gender discrimination is rife. Hourly-paid supervisor roles are often occupied by men, whilst women are paid piece-by-piece, often subjected to verbal and physical abuse, and deprived of social security benefits.

Child labour is not uncommon, nor are life threatening conditions or 20-hour days. Factory owners push wages ever lower, enforce overtime, and maintain conditions that are at best unsanitary, at worst, deadly. Some would call this efficiency improvement. Better to call it sweating 2.0. This time, gone global.

The Psychological Cost: Dependence

Source: Unsplash

Fast Fashion is, quite literally, addictive.

Studies have shown that when we bag a new bargain, dopamine reward pathways in the brain are activated. Dopamine is a feel-good neurotransmitter associated with addictions to smoking, drugs and caffeine. As clothes have become cheaper and more available, so has the opportunity to gain that addictive dopamine dose.

Misguided, for example, proudly states on its website that it releases around 1000 new styles a week - misguided indeed. To shift such vast quantities of stock, brands play psychological games. They make emotive, celebrity-backed advertising campaigns. They create a false sense of urgency through sales and change store layouts frequently, placing cheap items next to similar more expensive ones to create a false perception of value. They collaborate with ‘buy now, pay later’ apps to encourage impulsive spending, and so on. It’s behavioural psychology 101. The result: compulsive consumerism and fast fashion addiction.

Whilst brands make us want to spend more, their poor quality garments reinforce our practical need to. These days, clothes are designed to be disposed of, and quickly. Statistics show that the average American shopper now owns at least five times more clothing now than in 1980. For every five fast fashion garments produced, the equivalent of three end up on landfill sites or incinerated in under a year.

To use the words of economist Tim Jackson, we find ourselves deep within a system in which:

People are persuaded to spend money we don't have, on things we don't need, to create impressions that won't last, on people we don't care about.

It’s a great quote, to which I have to make just one small adjustment. There is one place on which our spending is leaving a lasting impression, and it’s that one we all depend on - our home, planet Earth.

The Environmental Cost: Disaster

Source: Pexels

From cotton crop into crop top, each step a garment takes from the farm to the fiesta has immense environmental implications. When displayed in carefully curated shop floors, it can be hard to imagine the farming, factories and ferrying behind our clothes. Yet the impacts of these processes are vast and wide reaching. From fossil fuel use, river pollution, depletion of fresh water systems, immense waste production, ocean plastics, the damage is ever increasing.

Climate Change

Source: Pexels

It is now hotter on our home planet than it has been for at least 12,000 years. This is, in no small part, thanks to the global fashion industry.

Soft fabrics in pretty pastel colours don’t immediately scream out oil and coal, but they are the base upon which most of our clothes are built. Increasingly popular synthetic fibres are produced using both coal and petroleum. Whilst they use less water than their natural counterparts, the energy required and CO2 emitted is higher.

Synthetic fibres also pollute. As an oil-based plastic, polyester does not biodegrade like natural fibres. It can stay in landfill waste for hundreds of years. When washed, synthetic fibres shed and eventually end up in waterways and oceans as microplastic fibres. As high-speed, low-cost fashion has come to dominate, so has the use of cheaper synthetic fibre such as polyester. If you check your t-shirt now, there’s a high chance you’re sporting at least some of the synth - it’s now estimated to make up 60% of garments globally.

As garments are being produced, they can travel many times around the world before they even make it to the shelf. Estimates show that fashion’s carbon impact industry has an impact carbon greater than Aviation and Maritime Shipping combined. Every new tonne of this carbon released pushes the global temperature average rise closer to the 1.5°C limit - a pathway at which we are already seeing irreparable damage.

Biodiversity Loss

From giant whales down to tiny bacteria, Earth’s species diversity gives and sustains life on our planet. Yet we are losing at an alarming rate. Pesticide-intensive fashion agriculture plays a major part in this demise.

As the demand for clothes has increased, so too has the demand for high turnover and fast-growing crops. This has led to a marked shift towards pesticide-intensive, biodiversity-destroying agriculture.

To produce the high turnover of cotton now demanded by the fast fashion supply chain, farmers use toxic chemicals in excess. These all but eliminate natural organisms such as fungi, insects or weeds. They contaminate the surrounding soil and water. They destroy insect populations, reduce soil fertility, toxify aquatic systems and leave them all but devoid of life. Environmental activist and scholar Vandana Shiva labels pesticides as ‘ecological narcotics’ as the more a crop receives them, the more it depends on them.

Communities

In China, the joke goes that you can tell the “it” colour of the season by looking at the colour of the rivers - a joke that, by now, has surely lost it’s humour.

For years, waterways which once served as the lifeblood of communities throughout Asia have suffered an unrelenting discharge of untreated wastewater from the dyes, heavy metals and other toxicants of surrounding clothes factories. Left with no other option, communities continue to use this water for drinking and bathing. Diseases such as cancer, gastric and skin diseases are endemic, but continue to go largely unacknowledged by polluting brands.

And it’s not just water abuse, but also water use, that affects vulnerable communities. Fast fashion is incredibly thirsty. To make just one basic cotton T-shirt, estimates show that it takes roughly 2,700 litres of water. That’s more than the equivalent of 25 bathtubs of water for every cotton T-shirt you own.

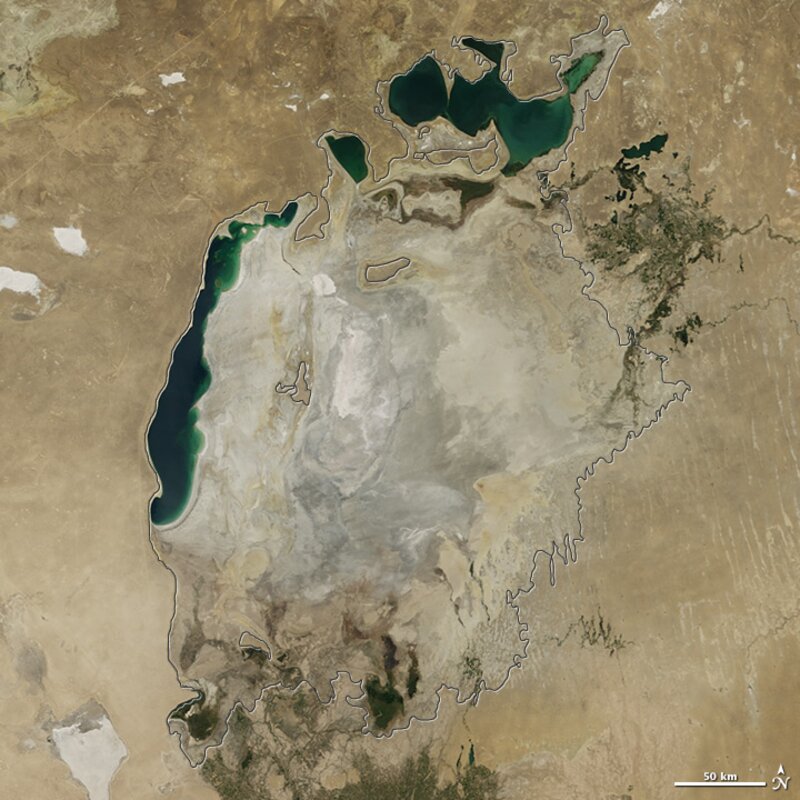

To take a more immediately obvious example, the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan was once the world’s fourth largest lake, surrounded by fishing communities and lush forests and wetlands. To sustain the garment export industry, throughout the late 20th century, the Government started to divert its fresh water to irrigate cotton crops and sustain the growing cotton industry. Fishermen lost livelihoods. Pollution from salt and dust from the lake bed caused widespread health problems.

In 2014, NASA released shocking images showing that the Sea was all but completely dried up. Whilst with careful restoration action the water is slowly returning, local communities are still suffering the impacts. Unemployment is high while thousands suffer respiratory diseases and long-term health impacts.

The Aral Sea, Uzbekistan, almost completely dried due to cotton irrigation. Source NASA Earth Observatory

Textile Waste

Mountains of Landfill Waste. Source: Pexels

Our fashion system causes tonnes and tonnes of fabric to be discarded, burnt or dumped in landfills. As much as 73% of material going into the clothing system ends its life in landfill or incinerated. Design bases tend to sit in Western countries within the EU or US, whilst production bases are in the global south. This means that mistakes, misunderstanding and misprints are commonplace. Often entire batches are thrown away before clothes even make it out of the factory.

After the point of sale, things aren’t much better. Poor quality garments mean clothes have to be replaced quickly, and more often than not carelessly. Approximately 85% of the clothing Americans consume is sent to landfills after use, rather than resold or recycled.

Often brands actively encourage this disposal cycle, in order to shift more stock. In 2017 and 2018, brands such as H&M, Burberry and Nike were exposed to burning mountains of unsold items in a bid to prevent the devaluation of their current stock. In H&M’s case, this was claimed to be as much as 19 tonnes of obsolete clothing, or the equivalent of around 50,000 pairs of jeans. In a system where mountains of unworn clothes are burnt and slashed, whilst the process that produced them destroys lives, it’s clear something is drastically wrong.

Fast Fashion: How Can We Avoid It?

Source: Unsplash

It is often said that if we would just stop buying so many clothes, everything would change. Whilst this has an element of truth, it also serves to remove the blame from the multinational brands that have so much power. Yes, we can make important changes as individuals, but we did not create the problem. Yes, our shopping habits must change, but our power as consumers extends far beyond just that.

Individual changes aren’t always easy, but it’s important to remember that no-one is a perfect ‘environmentalist’. Doing what you can and pushing your personal boundaries to live your values and create the change you want to see is key.

Fast fashion is a big beast to slay, but as consumers and citizens we have many lines of attack. If you feel inspired to act, here are just a few suggestions to start you off:

-

Demand transparency – If you can’t imagine a life without shopping; get informed and mobilise. Take part in Fashion Revolution’s #whomademyclothes campaign and fight against the system that locks so many workers into barely-paid, exploitative and dangerous work. Read the yearly Transparency Index, support the most sustainable brands and hold the others to account. The Fashion Checker is a great source which allows you to check any brand, for living wage, transparency and public commitments made.

-

Take the 30-wear pledge - When buying an item thing ‘Do I really need this item? Will I wear it 30 times? Is it of high quality and will it last?’ Check the quality of clothes before you buy them. Click here for a detailed guide on how to.

-

Shop second hand - Many cities are now populated with trendy vintage and traditional charity shops, whilst platforms like Depop offer access to a wide variety of used and vintage garments. UK-based Depop alternative Esooko offers second hand vintage clothes with proceeds going to environmental activist causes.

-

Repair, Rewear, Recycle, Rent – Organise clothes swaps. Don’t throw away clothes, find a seamstress in your area, or see if you can have a go yourself. Donate old clothes to charity. Rent the clothes you need for big occasions - Rent the Runway is perhaps the most well-known. By Rotation is another UK based peer-to-peer platform facilitating the sharing of people's personal wardrobes, for more casual, day to day wear.

And finally, and most importantly...

-

Rebel! –Fast Fashion brands will never engage in meaningful system change unless law forces them too, but fast fashion is currently low on the political agenda. Demand government action. Join XR, make some noise and make a difference.