Editor's Note : XR does not advocate for specific solutions to the climate crisis. We do seek to promote healthy, informed debate surrounding climate-related issues. This excellent, in-depth article is a prime example of how such debate can be had.

With thanks to Professor Paul Fennell.

Whether you’re for it or against it, carbon capture and storage (CCS) is something worth talking about.

Carbon dioxide - CO₂ - is a greenhouse gas; after release, it builds up in our atmosphere, trapping heat and causing temperatures to rise. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a technique which can be used to stop the release of CO₂ into the atmosphere during certain industrial processes.

If this is a completely new concept to you - don’t worry, you’re not alone. It is discussed by academics, engineers and some politicians, but is not marketed enough to be known by the majority of the general public. That’s a problem. These ideas shouldn’t be limited to the experts: they should form part of everyone’s vocabulary.

This article exists for you to make up your own mind about CCS. It is not designed to support or condemn CCS. This is an article which puts technology at its heart. I am an engineer. I want you to walk away from this article knowing that carbon dioxide can be captured and it can be stored.

The truth is… I have spent four years of my life trying to understand the technology and the debate surrounding it. We only have ten minutes. You will not be an expert by the end of this article, but you will know enough about the basics to understand the complexities of this subject.

Let's dive into the details together.

What is The Science Behind Carbon Capture and Storage?

Here is a very simple explanation of how CCS works:

Imagine a coal-fired power plant: the coal burns, releasing heat and gases. The heat is useful, producing electricity. The waste gases, mostly carbon dioxide and water vapour, must then be removed. The cheapest and most common option is to build a chimney - known as a 'stack' - to allow these gases to leave the plant.

What if you could separate those waste gases from the CO₂, keeping it away from atmosphere? That is carbon capture.

What if you take that separated CO₂and pump it underground? That is carbon capture and storage, or carbon capture and sequestration. Both terms are interchangeable, used in industry, and are often shortened to the acronym 'CCS'.

How is CO₂ captured?

There are three types of commonly-discussed capture types: pre-combustion, post-combustion and oxyfuel combustion.

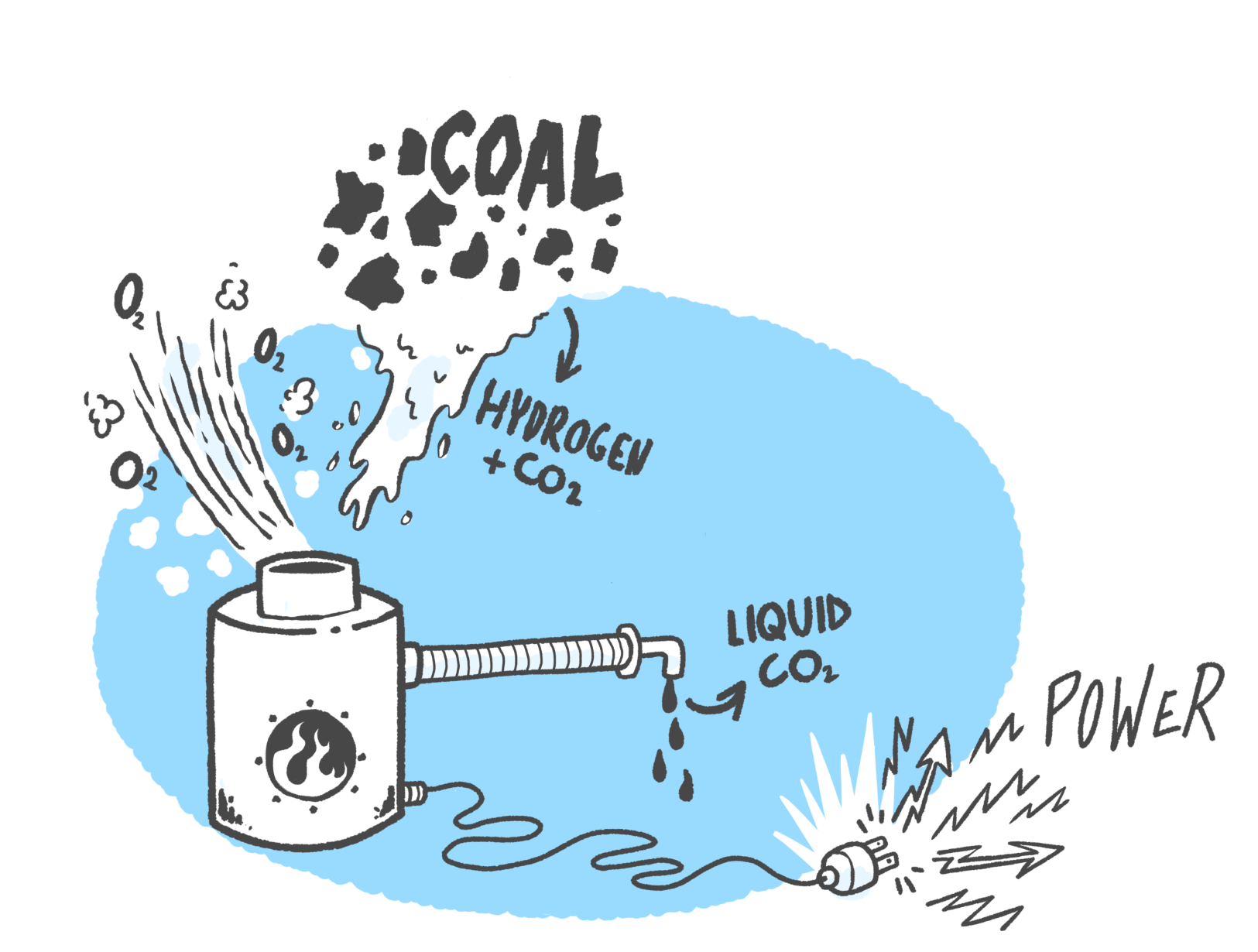

Pre-combustion capture works by exposing fossil fuels to high pressure steam.

Think back to our coal power plant: grinders crush up the coal, ready for reaction. Then, rather than burn it in air, the pipes pump out high-pressure steam instead. If we look at the chemistry for a moment, air contains oxygen (O₂) whereas steam is water (H₂O); oxygen (‘O’) is the key ingredient for burning fuel. Notice that oxygen has 2 Os and water has just one? Well, think of air ‘fully’ burning the coal, and steam ‘semi-burning’ it. When we semi-burn with water, we produce different products - carbon dioxide and hydrogen.

The CO₂ can be easily separated from the hydrogen. Pipes carry away the CO₂ for sequestration, and the hydrogen burns in a furnace, releasing energy for either heat or power.

This is the key benefit of pre-combustion capture: it can support the transition to hydrogen-based power.

Post-combustion capture is easier to visualise - in fact, it works like a vape.

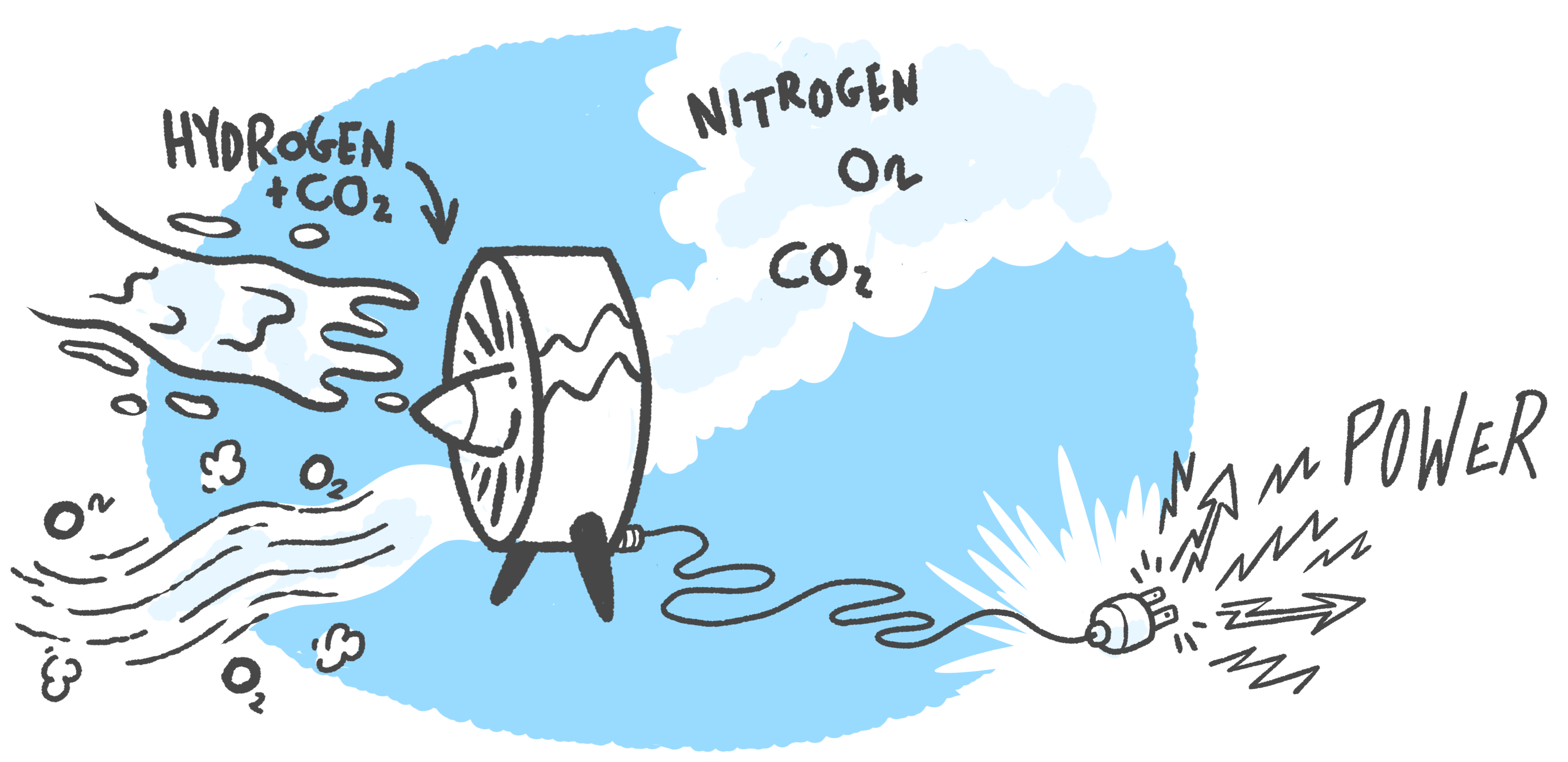

Back to the coal power plant. This time, the target is after combustion. The fossil fuel burns in air, producing the waste gases carbon dioxide and water vapour. Rather than venting through a stack, the waste gases travel to a ‘separation station’. The aim is to separate the gases once again. However, this is a different mixture of gases to pre-combustion: nitrogen from the air, carbon dioxide and water.

These waste gases bubble through a special pool of liquid (known as a ‘solvent’). The CO₂ ‘likes’ the pool, clinging onto the liquid and staying in solution. The other gases are not as keen, passing through the mixture easily and to the top of the vessel.

CO₂ clings less when heaters warm up the pool, releasing the gas and allowing sequestration.

Post-combustion capture is useful for existing plants, as the capture technology is relatively easy to add to existing infrastructure, and works at the end of the process.

Oxyfuel combustion is the newest capture technology and is yet to be used in industry. It works in a similar way to post-combustion capture, except that the fossil fuel burns in pure oxygen rather than air. [1]

Why burn fuel in pure oxygen? It is a more efficient way to produce CO₂, as well as reducing the production of common pollutants. There is so much CO₂ that once all the water vapour is removed, it can be pumped away immediately.

How is CO₂ stored/sequestered?

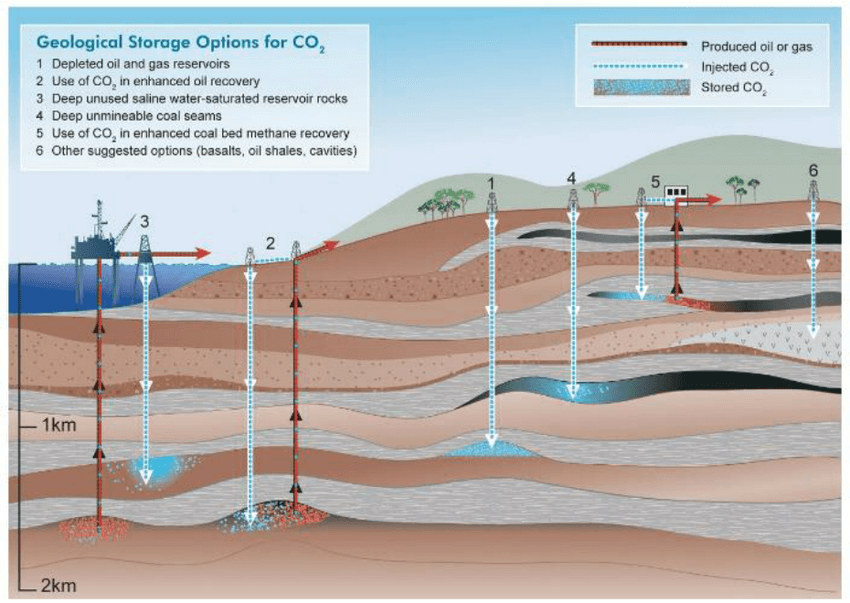

Pumps compress the purified carbon dioxide to high pressures, transferring it from the plant to the storage site, before pressurising it to such high levels that it acts like both a liquid and gas (known as ‘supercriticality’). As it has properties of both liquid and gas, scientists call it a ‘fluid’.

It is injected underground in this fluid state using a wellhead, where it remains trapped. (The technology is virtually identical to oil and gas drilling).

However, CO₂ cannot just be injected anywhere underground. There needs to be enough capacity to store large amounts safely and for a long period of time. This means there are specific types of geological sites used to store carbon dioxide:

-

Deep saline aquifers: layers of rock storing saltwater deep underground

Old oil and gas fields: where oil and gas were trapped millions of years ago.

Source: Tsar et al. 2013

The CO₂ initially remains trapped due to a layer of rock which sits above the fluid, stopping it from moving upwards towards the atmosphere. As time goes on, the CO₂ mixes with saltwater, dissolves, and eventually reacts with it to form rock. These processes can take millions, even billions, of years to occur.

Which industries can use carbon capture?

Carbon capture and storage can be used in any industry which produces carbon dioxide.

At the moment, the major industry is natural gas processing. Natural gas contains methane - the flammable fuel burned in our boilers - and CO₂. Rather than transport all the CO₂ to the consumer, it is easier to separate it at source.

Carbon capture can also be applied to several other industries:

- Chemicals production: for example, fermentation or coal-to-chemicals

- Hydrogen production

- Fertiliser production: fertilisers require hydrogen for production. If carbon capture allows the production of hydrogen, the hydrogen can produce fertiliser

- Steel production: coal is a key part of the process, which reacts to form CO₂

- Concrete/cement production: as the raw materials mix together, they react to produce CO₂

- Fossil fuel power stations: when the fuel burns, it releases CO₂

The Arguments For CCS

Carbon dioxide emissions will not be lowered enough by simply decreasing fossil fuel consumption alone. While the world transitions to low-carbon power, CCS allows us to capture carbon dioxide at source, ensuring it cannot reach the atmosphere and greatly reducing its harmful effects.

The effectiveness of CCS is clear when examining a real-life example: Boundary Dam in Canada, which is a CCS plant attached to a coal power plant.

The plant was designed to take in one million tonnes of CO₂ each year, and this month it captured CO₂ at a rate equivalent to 900,000 tonnes per year.

Using figures published online, I was able to calculate that Boundary Dam would have released 59,000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions this month without CCS capabilities. However, with the help of carbon capture, this figure was reduced to 7,000 tonnes. In other words, 52,000 tonnes of CO₂ ‘avoided’ release into the atmosphere [2].

That is a lot of carbon dioxide which will not need to be dealt with further down the line, when its harmful effects are a lot harder to avoid. Importantly, it is not only in the energy sector that emissions can be reduced through CCS.

Perhaps the most useful aspect of CCS is that it can be applied to industries which cannot, at present, be decarbonised: notably, cement and steel.

Steel is made by heating iron oxide with carbon, and carbon dioxide is the waste product. Concrete and cement are central to our everyday lives, but their production releases CO₂ without any burning of fossil fuels. CCS allows the production of these fundamental materials - used in housing, dams (both hydroelectric and reservoirs), bridges, wind farm construction, and other large civil infrastructure projects-while greatly reducing their emissions rate.

Is this technology currently in use?

CCS not only exists, but the number of sites is growing year on year. There are currently nineteen sites in operation, with thirty more under construction, proposed or waiting for approval.

Major universities such as Imperial College London and MIT, and oil companies like Exxon Mobil and Chevron are pushing forward development. Yes, Big Oil is interested...but more on that later.

I’m convinced! Sign me up for CCS

CCS does offer some advantages. Fewer CO₂ emissions go into the atmosphere, reducing the impact of burning fossil fuels which, as we know, leads to global warming. Plus, it can do this incredibly efficiently when designed and put in place properly.

The Arguments Against CCS

However, it would be wrong not to question CCS at all. Let’s run through some disadvantages of CCS technology, before you make up your mind.

CCS will not eliminate all carbon dioxide emissions

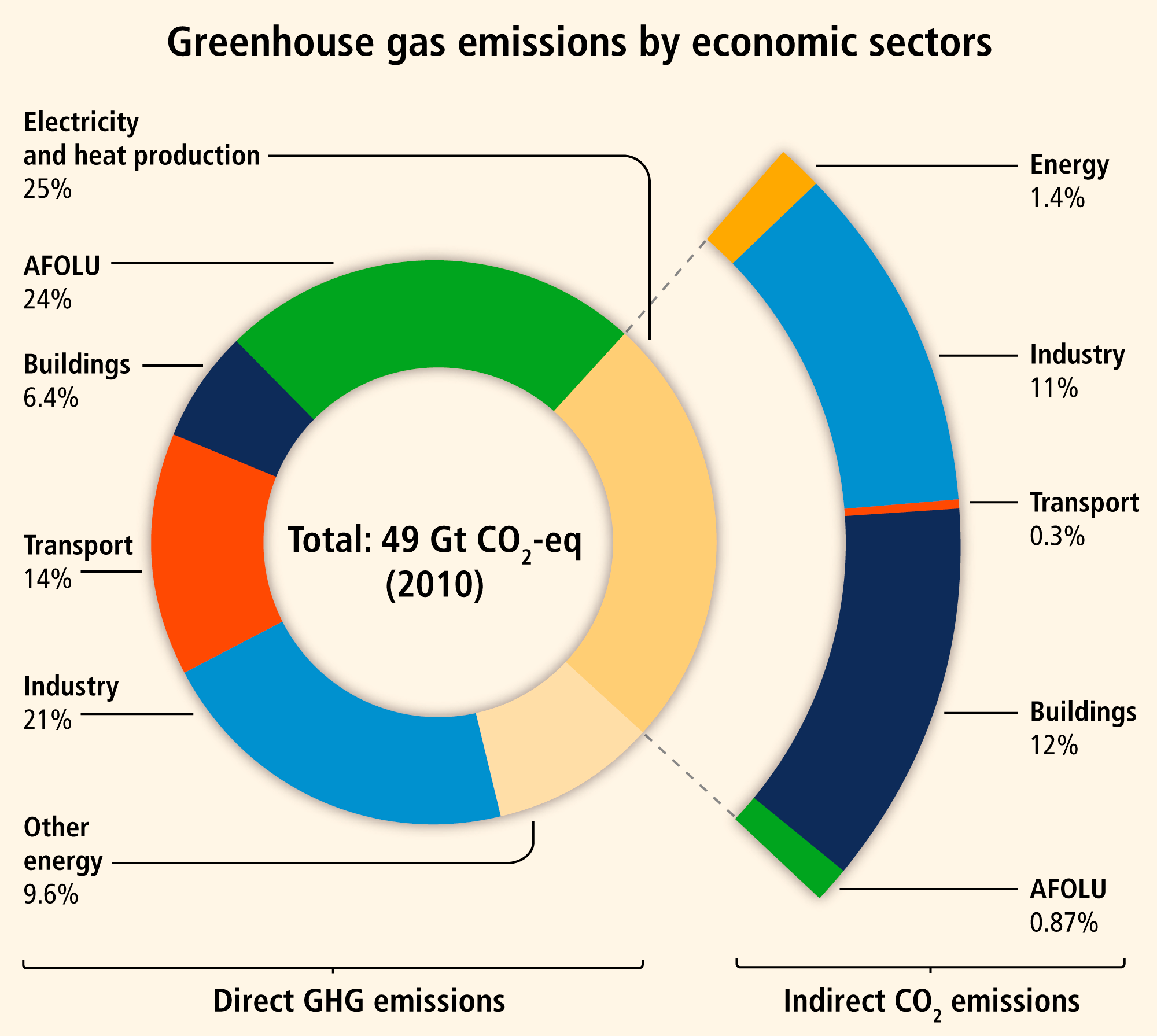

Source: IPCC, Synthesis Report AR5, Fig 1.7

CCS is limited because it can’t be applied to all CO₂ emissions.

For example, forest fires and agricultural practices make up 25% of emissions. CCS cannot be applied here because combustion is unplanned.

CCS is also difficult to apply to the transport sector. Let’s take the automotive industry: there are approximately 1 billion cars worldwide, each releasing carbon dioxide.

In order to store this carbon dioxide on the individual level, each vehicle would require its own collection and storage unit. The carbon dioxide will accumulate, making the car heavier, meaning you need more fuel, meaning you produce more carbon dioxide. Plus, even if you were to make these changes to individual vehicles, then what? Everyone would have to have a carbon dioxide pipe in their homes; there would also have to be local and central hubs to dispose of this personal CO₂ collection, and so on...

In other words, it is far easier to capture carbon with a small number of large producers than with a large number of small producers.

(As a side note, this is another way in which electric cars help to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Factories can easily capture the carbon dioxide when oil is burned in a power plant to produce electricity. It is practically impossible to capture tiny amounts of carbon dioxide when petrol is burned in your car.)

CCS is not cost-effective

CCS is not a moneymaker. Not only that, it requires massive up-front investment for relatively little return. Companies typically do not implement CCS because they have little incentive to do so.

There is a world where CCS can exist, but it relies heavily on the world having a carbon tax. If countries and companies have to pay to release CO₂, they will seek out ways to stop releasing it into the atmosphere.

Some countries already have carbon taxes, and these are the countries in which CCS is being implemented - Norway being the primary example. However, it is also likely that these projects involve something called ‘Enhanced Oil Recovery’ (see below), as oil (usually) produces profit.

CCS takes a lot of time to build

Also, there are issues with construction. Carbon dioxide needs to be transported somehow, and building the additional infrastructure to do this takes years. This could reduce its effectiveness, depending on how quickly we can move towards a future of low-carbon power. However, it is possible and some regions, such as Teesside in the UK and Rotterdam in the Netherlands, are planning to have completed construction within the next five years.

CCS continues the fossil fuel cycle

Back to Big Oil: they have a vested interest in CCS, due to something known as ‘Enhanced Oil Recovery’ (EOR). They can use carbon dioxide from pre-combustion capture, compress it, inject it again and force out more oil from an oil well. Companies can produce more oil per well, making wells more profitable. This increases the number of wells which are considered profitable for the company to exploit, therefore more oil will be produced and we continue the cycle of oil dependence.

It is important to note: there are still carbon emissions from EOR. EOR allows oil companies to harvest more oil profitably over a longer period of time, meaning more carbon dioxide could be released than if oil companies are limited by their current oil production. In other words, it may be more effective to kill fossil fuels quickly than let it die slowly.

However, there is some balance to this argument. Significantly more carbon dioxide is stored through EOR than is released by burning the crude oil that comes out. It is a much better option than crude oil production without EOR - providing that total oil demand decreases with time. Furthermore, EOR means companies want to fund carbon capture research and development which benefits everyone in the long run, and the implementation of EOR has also proven the safety of CCS on a large scale.

And while EOR currently generates the most profit for oil companies, if economies change, so will their approaches to carbon capture. In other words, they may choose to progress from EOR to ‘regular’ carbon capture and storage… with the introduction of subsidies or technological innovation.

This being said, there are sound arguments against this continued reliance on fossil fuels in a rapidly heating world.

Is CCS just another tool to prop up the fossil fuel industry?

CCS succeeds in decarbonisation models partly because it is the smallest possible change from the current infrastructure. There are other options for energy decarbonisation. However, it is ‘more secure’ to keep infrastructure as it is, and this desire is driven by everyone, whether they be politicians or members of the public.

The money that could be spent on these other options is put towards fossil fuel industries. $150 billion was spent by global governments subsidising oil in 2019 alone. Installing such complex energy decarbonisation systems may currently have high political and financial barriers to overcome, but countries will lose more money if they don’t change tactics as soon as possible.

Even ignoring the impact of climate change on national economies, there is still an economic case for renewable energy. The price of renewable energy is similar to fossil fuels (with some conditions), and CCS will actually make fossil fuels less competitive.

Should companies really be investing in expensive ways of reducing carbon emissions, when they could be investing in available green technologies and eliminate them completely?

CCS has environmental risks

There are some environmental risks associated with the storage of carbon dioxide.

Carbon dioxide is typically stored under oceanic rock. If the rock is placed under too much pressure, it may fracture, or earthquakes may cause rock layers to shift, leading to carbon dioxide leaks. If carbon dioxide leaks into the oceans it causes ocean acidification - a process which is already happening at alarming rates - and destroys marine ecosystems with devastating effects.

It is important to note that no sites have leaked in the short-term at present. In fact, one CCS site was shut down rather than risk putting the rock under too much pressure.

Right, that was a lot of information. Let it all sink in.

You may have one of three opinions of CCS:

1: On balance, this seems like a good idea

This view covers a range of opinions. Maybe CCS should be applied to every single industry it possibly can. Maybe it should be applied to essential industries that cannot otherwise be decarbonised. Maybe the lure of an entry route into hydrogen is too much to resist, and it is a good transition to a cleaner world.

If this is your view, the million-dollar question is: why aren’t all capable countries implementing CCS? In short, it comes down to an individual government's priorities. Ten countries have chosen to implement CCS. Hundreds have not.

Since CCS is an idea usually left to academics or engineers, there may not be enough public opinion on CCS to make it a priority in some countries. This should change, and is why CCS needs to be discussed by citizens in Citizens’ Assemblies.

2: No, thank you. I don’t want to prolong fossil fuel use.

Fair enough. Sometimes, governments need to take large strides to action rather than walking on their tiptoes. CCS is the equivalent of a half-step. There are different ways to implement decarbonisation - some of which I hope to discuss in future articles.

Again, there is no clear answer. These alternatives should also be part of the discussions by citizens within their Assemblies.

3: I’m just not sure.

I would be surprised if ten minutes would convince you to feel strongly either way. Governments have not figured out their stances after several years! To pick just two examples, the Netherlands has flip-flopped on the issue, while the UK government has been indecisive, leading to estimated billion-pound losses.

The truth is that global governments are currently unlikely to spend large amounts of money on projects which have little public interest and aren’t economically profitable in the short-term. If, however, public opinion were to change, there is potential for CCS to be pursued more openly.

Regardless of your take on the CCS debate, carbon capture and storage should at the very least be part of the discussion.

It should form one of many urgent discussion topics for citizens’ assemblies: Extinction Rebellion’s third and final demand.

Sign up to the Rebellion here!

Footnotes:

[1] With some recycled CO₂ to make it slightly less combustible.

[2] Boundary Dam has captured at the rate of 890kt/y this month. Capture efficiency is 90%. The efficiency penalty is 20%. (The efficiency penalty described how much extra carbon dioxide must be produced to capture the remaining emissions). Therefore: Originally 712 kt/y released; 801 kt/y can be captured; 89 kt/y is released now; carbon dioxide avoided: 623 kt/y, or over 85% of original emissions.

Further Reading

https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/resources/global-status-report/ - the current CCS picture

https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2020 - how carbon capture fits into the wider picture

https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions - the future for carbon capture

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876610217320933#:~:text=CCS will not advance without significant public investment,CCS play a major role in this respect. - the politics of CCS, and ways to depoliticise it

https://www.edx.org/course/climate-change-carbon-capture-and-storage - more depth about the technology

https://www.catf.us/2019/06/leveraging-enhanced-oil-recovery-for-large-scale-saline-storage-of-co2/ - more about EOR

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2019/11/13/20839531/climate-change-industry-co2-carbon-capture-utilization-storage-ccu - a fantastic series by David Roberts which goes into even more detail about CCS