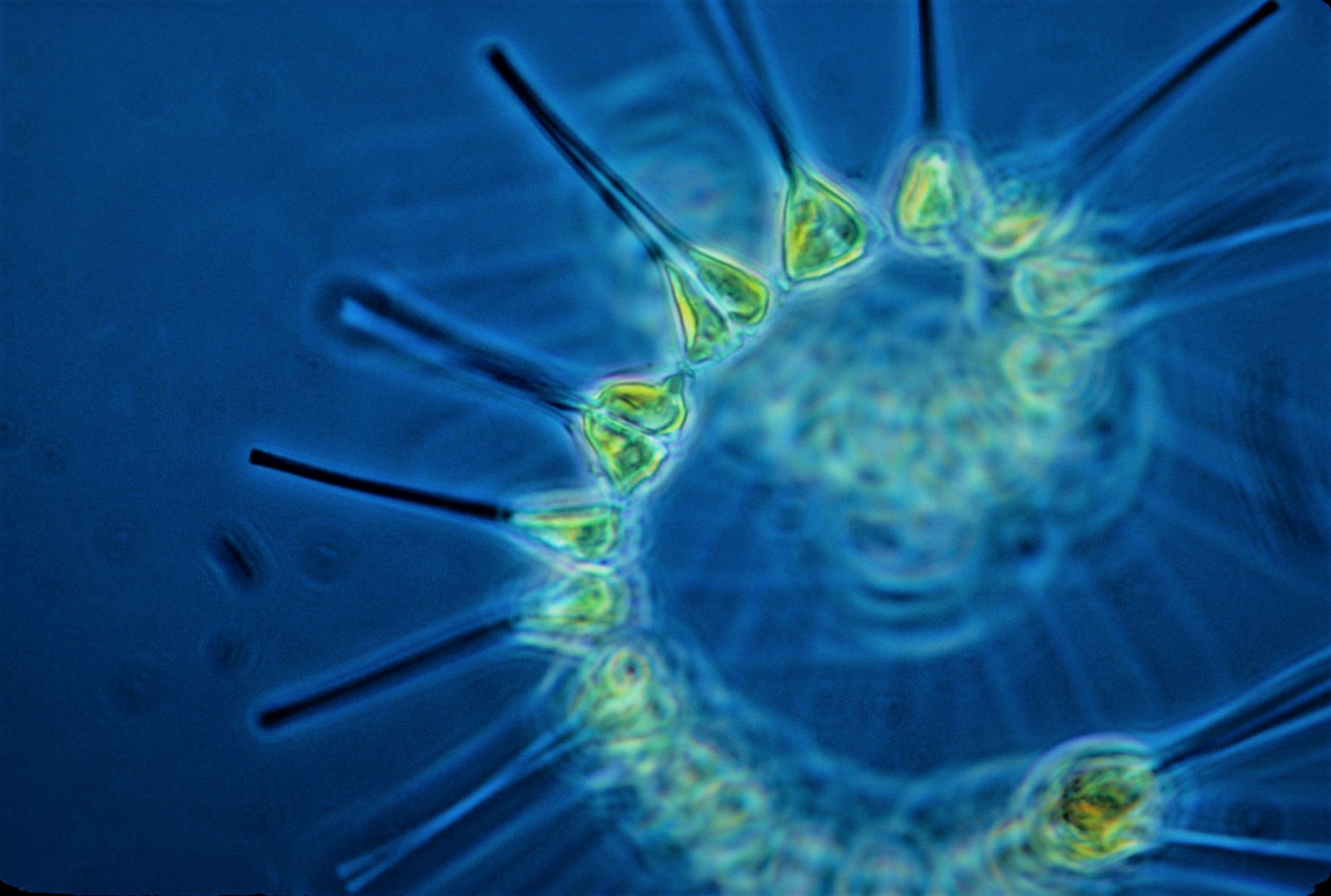

It’s bizarre to think that billions of phytoplankton floating across the oceans are keeping us all alive.

These remarkable microscopic plants produce more than half of Earth's oxygen, they draw over 100 million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the oceans every day, and form the base of a food chain for all marine life. That’s some impressive multi-tasking.

Phytoplankton, NOAA

The diversity of life on land is astonishing enough; in the oceans it’s unimaginable. For an illustrative peek under the surface; there are over 8,500 known species of sponges, more than 50,000 of crustaceans, and at least 85,000 of molluscs. Distinguished marine biologist Professor Frederick Grassle estimated the number of marine species to be between one and ten million.

Ocean life ranges from bacteria just thousandths of a millimetre wide, to a blue whale 108 feet long (33 meters) weighing 220 tons; from a frigate bird soaring two-and-a-half miles above the sea’s surface, to a snailfish living over five miles below it.

As well as being home to an immeasurable diversity of life, oceans are vital in regulating global climate systems. Their currents distribute the sun’s heat, moderating temperatures and keeping the land habitable. Oceans are also a powerhouse of everlasting clean energy which can be harnessed to replace fossil fuels, so they can play a crucial role in society’s transition to a green and equitable economy.

New antibiotics and drugs to treat cancer, HIV, and malaria are being developed from marine organisms. Over 200 million people are directly or indirectly employed in marine fisheries and approximately three billion people depend on seafood as their main source of protein.

Healthy, life-filled oceans give us food, livelihoods, energy, medicine, hospitable climates, and even the air we breathe. In short, they make all life on Earth possible.

But, as we know, the oceans are in trouble, beset by a daunting range of threats.

This article looks at some of the approaches being taken to tackle them – such as creating marine protected areas and coastal communities taking grassroots action – and asks: are these approaches sufficient? And, if not: what more can we do to defend the sea, in the face of an escalating climate and ecological emergency?

Frigate bird, Lorenzo Mittiga, Ocean Image Bank.

Identify the problems

Despite our complete dependence on them, the world’s coasts and oceans have endured our destructive ways for centuries, and since industrialisation, the damage we cause has accelerated.

The way people are using the sea and exploiting its resources is destroying precious undersea and coastal habitats; causing mass cruelty, distress, and death to wildlife; and exacerbating the climate crisis. These are the shameful truths of our relationship with the sea – showing neither an essential respect for nature, nor basic common sense.

The evidence is in:

• Wasteful, illegal, and destructive fishing, where 30 percent of commercial fish species are overfished and 38.5 million tons of accidental by-catch is killed each year;

• The harm to marine life caused by underwater noise from shipping, sonar, and mining

• The many tons of discarded fishing gear left in the sea;

• The practice of bottom trawling – where fishing boats drag heavy nets along seabeds – releasing huge quantities of carbon dioxide;

• Contaminant and damaging fish-farming;

• The millions of sharks killed for their fins;

• Human rights abuses and corruption.

Serious problems also stem from what happens on land: by agricultural run-off, industrial discharge, and plastic waste polluting rivers and seas; and by the effects of burning fossil-fuels, which lead to seas warming, ice-caps melting, sea levels rising, more extreme weather events, and ocean acidification.

It amounts to a sprawling, multi-front ocean onslaught.

Nicolas Job,Ocean Image Bank.

The burning question is: how can we protect coasts, oceans and marine life more effectively than we have done so far?

Marine Protected Areas - a silver bullet?

Creating marine protected areas and marine reserves is widely regarded as the best way to defend the sea from further harm.

In a marine protected area (MPA), activities such as fishing and dredging are restricted, while in a marine reserve, everything is fully protected and commercial activities are permanently prohibited (they’re also called “no-take” zones).

Nature recovers surprisingly quickly if it’s left alone; and when sea waters are undisturbed, life returns — frequently in abundance.

In Tortugas Ecological Reserve in Florida, for instance, scallops increased fourteen-fold after five years of protection. A study published in 2009 found that on average, biomass (the mass of animals and plants) more than quadrupled over three years within a marine reserve. However, nature’s recovery can take much longer, as the story of Monterey Bay illustrates.

As well as the ecological benefits, marine reserves bring economic and social advantages. Older, larger fish tend to produce far more eggs than smaller, younger ones. By providing a safe haven where they can mature and reproduce, fish populations swell and may boost the catches of fisheries in nearby waters.

Renata Romeo, Ocean Image Bank.

Over the years, scientists and conservation NGOs have been steadily raising the marine protection target, and today they are calling for 30 percent of the global oceans to be kept safe within a global network of MPAs.

However, there are drawbacks to designating marine protected areas as the solution to this global problem:

1. Abstract boundaries

Due to the very nature of water and marine life – in particular, their mobility and unpredictability – applying land-based thinking to the sea as a conservation strategy has limited success, unless the protected area is very large. The plastic waste and pollutants we want to keep out, or the wildlife we want to keep in, pay no attention to boundaries on a map. Sharks for instance, may be safe from the shark-finners within a reserve, but not when they swim outside it.

2. Obstructive bureaucracy

Establishing a reserve or marine protected area can be a long-winded process, fraught with bureaucratic obstacles. There is always opposition from various sectors, such as the oil, gas, and aggregate dredging industries, and too often governments defer to their demands. Most commonly, resistance comes from the fishing industry, even though the evidence shows that having protected areas leads to greater numbers of fish for the industry to catch and sell.

3. Size and location

Because our understanding of marine ecosystems is incomplete, there is also the issue of where best to designate an MPA or marine reserve and how big it should be. The life stages of many marine species occur in different locations, which can thwart efforts to protect them. One stage may happen within a reserve, while the next could occur in adjacent unprotected waters. An example is the Caribbean Spiny Lobster, which lives in a variety of habitats during its life, including mangroves, reefs and the open ocean.

Although there are thousands of protected areas around the world, few are large enough to be very effective. Their location may also be determined by wherever is least inconvenient for industries like fishing and oil exploration, and not by the area’s ecological importance, which smacks of environmental tokenism. In these cases, economic interests are still overriding the essentiality of nature, indicating that policy-making priorities haven’t moved forward.

4. Lack of genuine protection

Many MPAs and reserves are ‘protected’ in name only and provide no more protection than in the rest of the sea. It could be that regulations aren’t monitored and enforced; or that there’s no management plan in place; or, that restrictions on human activities are so minimal that they make no difference.

5. Avoiding the Problem

While recognising how valuable marine protected areas can be, their fundamental shortcoming as a conservation strategy is that safeguarding parcels of water doesn’t address the problem we’re trying to solve. It doesn’t stop the existential threats to the oceans.

Top-down partial protection policies help maintain the status quo, because they allow over-extractive and often barbaric commercial practices to continue beyond the boundaries of protected areas. Looking beyond those boundaries is essential if we are to safeguard the seas.

Thijs Stoop, Unsplash

What about the other seventy percent?

If we can plan to protect a third of the oceans, we can plan to protect all of them. Seas will still be fished, cargo shipped across them, jobs created and profits made, but the way industries and communities use the sea would be carefully regulated and restricted in order to safeguard all marine environments and their wildlife.

Law enforcement systems and technologies have been available for several years and are steadily advancing.

With commercial fishing for instance, compliance controls include fitting vessels with a Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) and Automatic Identification System (AIS) to monitor activity and track their positions at sea; independent observers on board; patrol ships in operation; strict licensing rules; and a catch documentation program to prove that fish were caught legally.

These are some of the measures used by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources to control commercial fishing and maintain healthy ecosystems in the Southern Ocean.

Before I’m labelled an idealist, consider this: the world’s oceans and marine life are already protected by international law.

Several conservation agreements are in place, such as the UN Fish Stocks Agreement; the Convention on Biodiversity; the UN World Charter for Nature; the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change; the International Whaling Commission; the Antarctic Treaty – and since 1994, by the United Nations Law of the Sea – specifically by Articles 61, 117-120, 192-216 and 242-244 (1).

“States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment… [and]...take all measures necessary to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment. [They must] protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species and other forms of marine life” and should work together to agree on “international rules, standards and recommended practices… for the protection and preservation of the marine environment.”

Excerpts taken from the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas, Articles 192, 194, 196 & 197. (1)

Davi Mendes, Unsplash.

You may be wondering: if we have laws to protect them, why are the oceans facing so many threats?

The answer is: ignored and unenforced law is much the same as having no law.

As with other environmental protection commitments, (such as the Paris Agreement to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and the Convention on Biological Diversity targets to stop the loss of biodiversity) governments, perpetually under pressure from corporate lobbyists, have mostly reneged on their targets and assurances to ensure citizens have safe and habitable environments in which to live, and enable nature to regenerate and flourish

Thankfully, there are exceptions.

The Montreal Protocol is the international treaty agreed to end the production of substances that were breaking up the ozone layer, the stratospheric mantle that shields Earth from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

It’s widely considered to be the most successful environmental treaty, having phased out over ninety-five percent of the ozone-harming chemicals. It’s also the first United Nations treaty with the participation of all countries and has almost full compliance. The Montreal Protocol shows that it is possible for the global community to pull together and take relatively swift action to protect the natural world – a fact that’s both encouraging and exasperating in equal measure.

Ripples becoming waves

In the absence of sufficient state intervention, people find other ways to solve problems, or to safeguard their ways of life. In many coastal communities people are protecting inshore fisheries and marine habitats themselves.

Locally led marine management (also called community-based marine conservation) is a citizen-driven movement which began in Fiji in the 1990s.

Years of uncontrolled commercial fishing, of pollution, and of removing live corals and tropical fish for the aquarium market, had left much of Fiji’s seas and their wildlife in decline. Residents in the village of Ucunivanua decided to take action. They closed off 60 acres of nearby mudflats and sea-grass beds for three years. It was to be Fiji’s first locally managed marine area (LMMA) and the difference it made was dramatic. Within seven years clam populations increased 24 times over.

The notion that ‘experts’ – scientists, managers, and politicians – know best, was debunked.

Fishers and other members of the community were making management decisions, based on their needs, their priorities, and their ecological knowledge. News of Ucunivanua’s initiative spread around Fiji and prompted others to follow suit. Success has been breeding success, and the locally managed marine conservation model has moved way beyond Fijian shores.

King Penguins of the Southern Ocean. Paul Carroll, Unsplash.

Similar projects are running over the South Pacific, to Indonesia, the Philippines, across the Southern Hemisphere from India to Kenya, Mozambique, and Madagascar, as far as South America and Central America, to Mexico and Canada, and from North Africa to Europe.

Grassroots marine conservation is a very positive development in the battle to rescue and conserve the oceans, and as it gathers momentum, may be achieving more than the well-intentioned international agreements which all too often, governments across the world then disregard.

From the South Pacific again, comes more good news for the sea. Recently, the small South Pacific island state of Niue made the bold move to designate all of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) a protected area — which covers a generous 317,500 sq km (122,000 sq miles) of the Pacific ocean. Previously, the Cook Islands and Palau took similar steps, effectively outlawing damaging practices in 100 percent of their waters.

These island nations are providing a working model of ocean protection which could eventually be rolled out globally.

For the natural world as a whole, light is on the horizon in South America. Ecuador has enshrined the Rights of Nature into the constitution, and Bolivia passed the Law of Mother Nature to 'establish the vision and fundamentals of integral development in harmony and balance with Mother Earth to live well’.

Spotted eagle rays. Amanda Cotton, Ocean Image Bank.

There are many cases of new laws bringing about more enlightened societal norms and attitudes, from relatively small improvements like banning smoking in public spaces, to major advances such as outlawing child labour and slavery. And, although we are at an early stage of change, states beginning to recognise and defend nature’s rights is a major step in the right direction.

It follows that by putting protective laws into practice, society is likely to become more respectful and appreciative of the oceans and their wildlife.

Everything people have to do with the sea can be based on a simple universal principle: to use all of it responsibly – without emptying or polluting waters, without wrecking marine habitats, without needlessly killing millions of wild animals.

As coasts and oceans regenerate, waters will become cleaner and fill with fish to eat, to sell and crucially, to reproduce. Undersea habitats can recover, large-scale cruelty can end, wildlife can return, and coastal communities reliant on the sea can prosper.

In simple terms, it’s time to ditch the paradigm of plunder and protect the whole lot.

What can YOU do for the sea?

Most of us know about the plague of plastic in the sea and the importance of cutting out single-use plastics, but here are six more actions you could take:

- Learn about the sea and marine life, about conservation projects, and why healthy oceans are so important – be inspired, motivated, talk to friends and family and get them interested too.

- Read labels before buying. For example, many household cleaning, DIY, and personal hygiene products, and most sunscreen creams contain chemicals which harm or kill marine life.

- Boycott farmed salmon and warm-water farmed prawns and shrimp, because of the serious environmental damage caused by their production; and find out where the fish you consume comes from.

- Support a marine conservation organisation, either with a regular donation or as a volunteer.

- Vote for, and actively engage with, the electoral candidate committed to doing the most for nature.

- Join Extinction Rebellion or Ocean Rebellion and take part in peaceful civil disobedience to pressure governments to address the climate crisis and biodiversity loss.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(1) The USA took part in the Law of the Sea negotiations and signed the agreement, but hasn’t yet ratified the treaty because of limits put on deep seabed mining. However, the US follows the Law of the Sea as customary international law.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Deb Rowan Wright is a researcher and writer on ocean conservation policy. Her book, Future Sea: How to Rescue and Protect the World’s Oceans, presents the case for 100 percent global ocean protection.