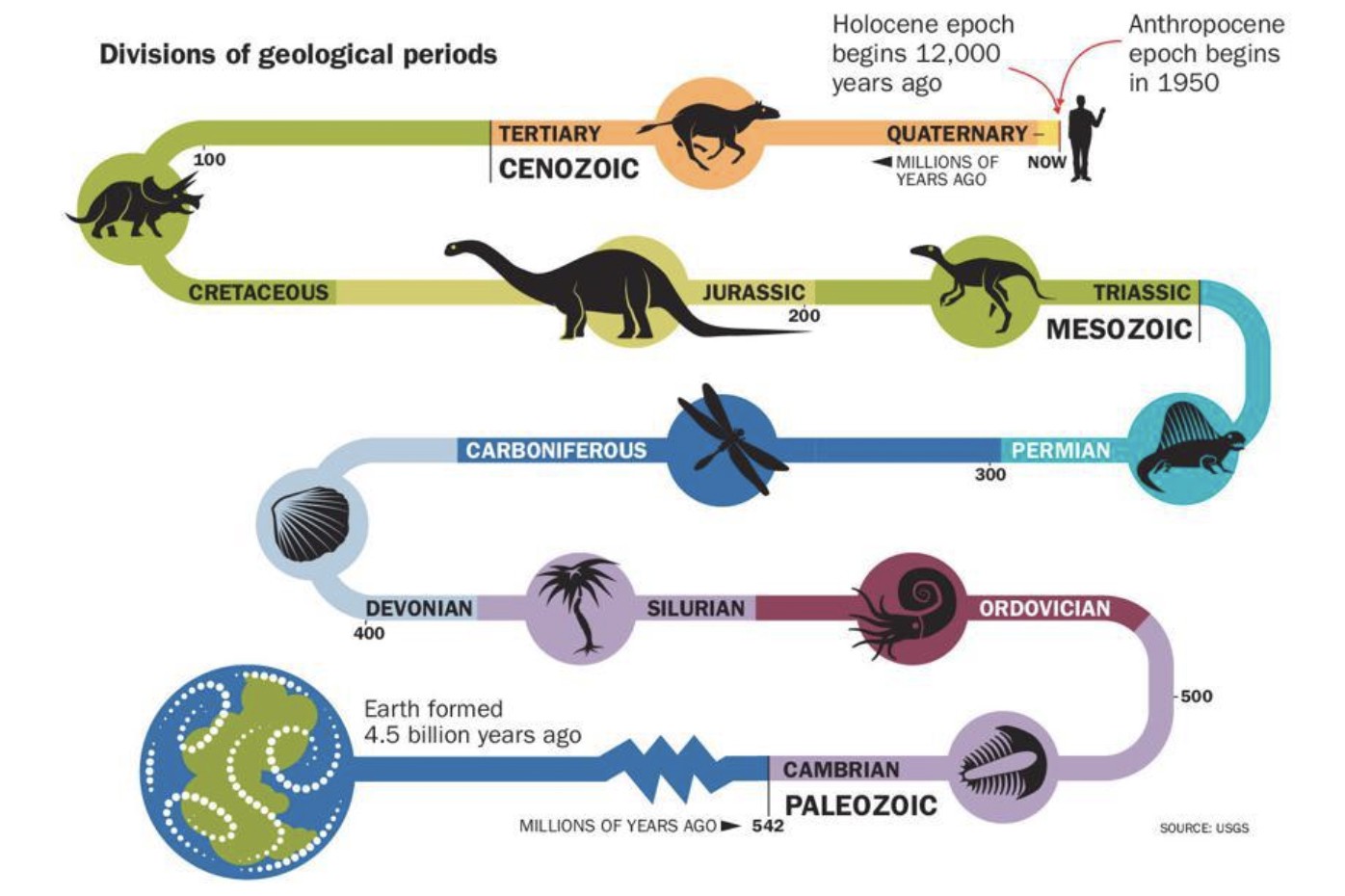

Anthropocene. Ever heard that word before? It’s new(ish). The terms Holocene and Pleistocene might sound more familiar; they’re geologic names for epochs. An epoch is one of the smallest slices on the geologic time scale (GTS).

Briefly, the debate about whether to use the term Anthropocene for our current epoch is between folks who wanna hold onto Holocene (which began around 12,000 years ago), and those—including us XR rebels—who say we must update to Anthropocene. Marked by the explosive uptick in toxic emissions, the Anthropocene began in 1950. For us, it’s a 20th century line in the sand.

Among the Holocene holdouts, though, some have a huge financial stake in the rest of us keeping our heads in the sand.

Or elsewhere.

Photo: author.

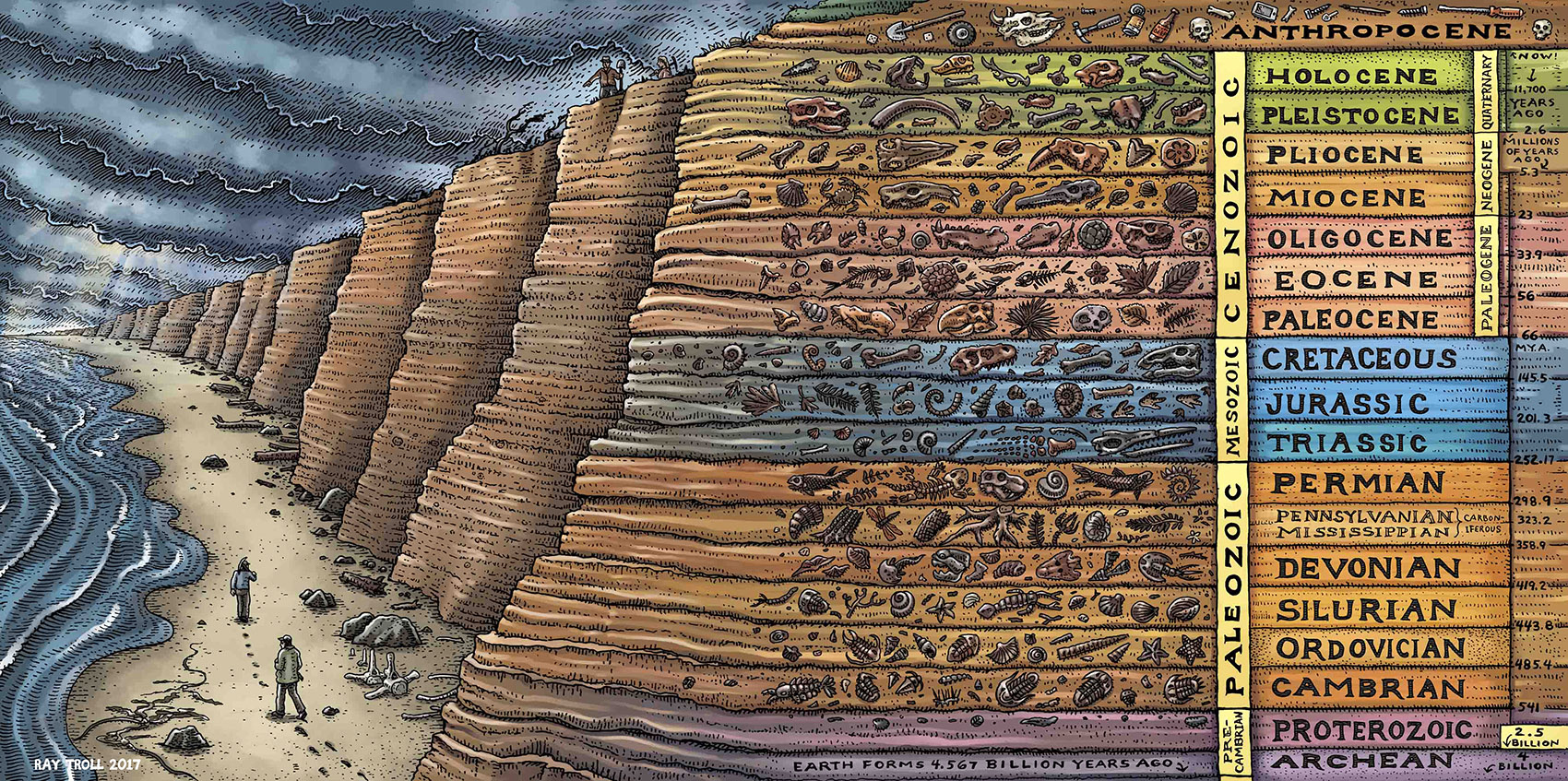

This diagram, from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), provides a pretty good path of Earth’s existence, showing how recently the Holocene and Anthropocene epochs—and we peeps—appeared. Kind of amazing all that we have done—for better or worse—in such a relatively short amount of time, but more on that in a bit.

What’s in A Name?

Humans like to name stuff: each other, places, plants, animals, objects, and historic events, to name a few. Names help us remember and distinguish things, even if the name we’ve chosen seems odd. Take, for instance, the red-bellied woodpecker.

Red belly. Really? Huh. Bluebird. Agreed. (Mostly.) Photos: author.

Yet, if a name does help us understand—and is accurate—that’s all to the good, right? Well… what if a name makes sense, yet implies blame? Massive, no-doubt-about-it, world-destroying blame? Even, or especially—if many of us never even heard of it?

So, let’s examine this word, Anthropocene, why it’s so controversial, and why the overlords of the underground non-renewables would not want you to know it.

The Definition

The prefix, “anthro,” means human.

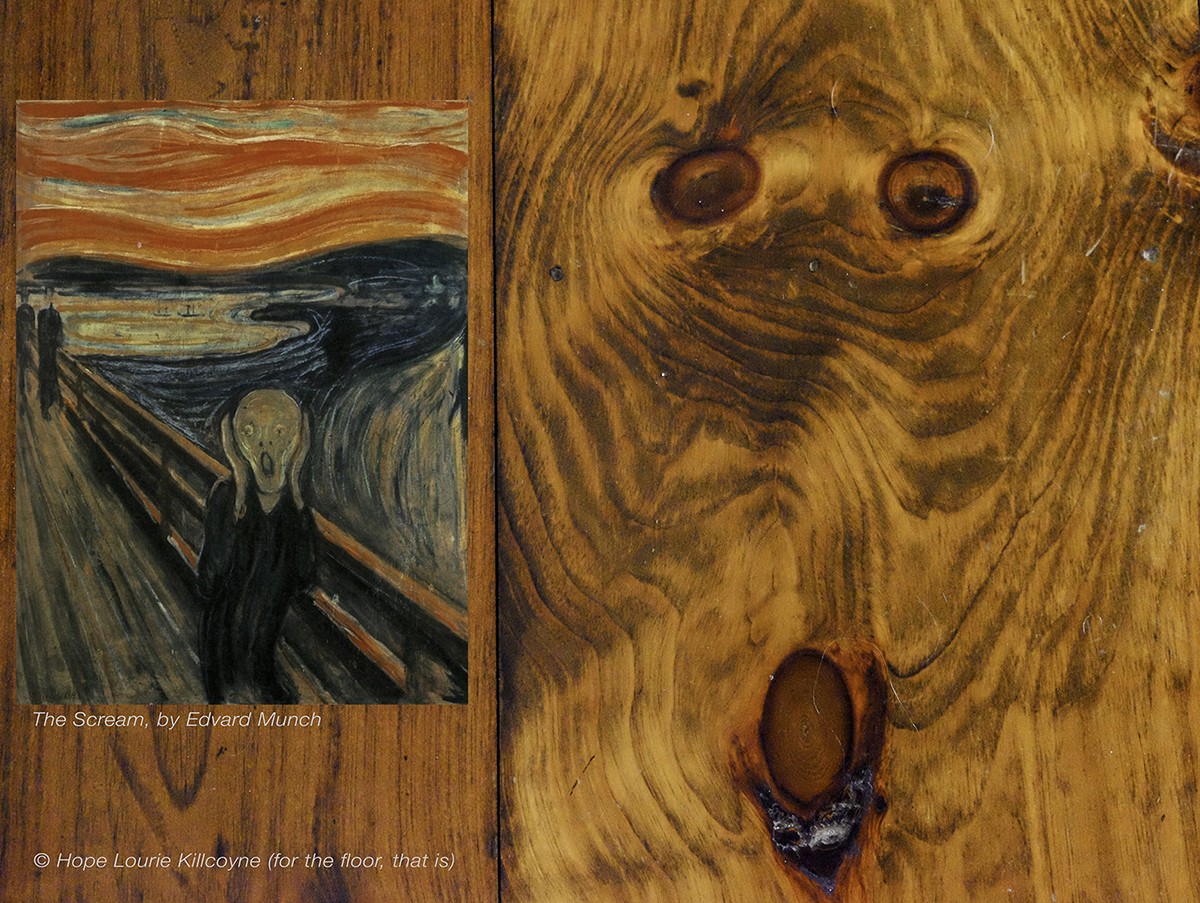

You know anthropomorphization. It’s like when you look at a floor, and see a face.

Yup: that face.

Or, when you talk to your dog or cat, AND answer back for them.

The suffix, “cene,” means new or recent.

Seems as though the suffix doesn’t make sense, right? Case in point, the Pleistocene epoch—the one before the Holocene? It began nearly three million years ago.

However, names in the world of rock layers (stratigraphy) aren’t always scientifically meaningful; they can even be seemingly random, or certainly obscure. (The Silurian period gets its name from an old Welsh tribe. Go figure.) But the Anthropocene—the recent impact of people upon our planet—from 1950 on—is rock solid.

The Importance of Perspective (Be it of Time and/or Distance)

It’s hard to think long term. That’s kinda programmed into us, so no judgment. How so? Well, say you’re 19 years old. If you start thinking about your own mortality, let alone that of other animals AND the world, how are you gonna win a game of Fortnight or Among Us? Go on a date? Get up in the morning and start those 10,000 steps? Do ANYTHING, for crying out loud?

That said, looking back is absolutely necessary to get a handle on what lies ahead. As it’s probably easier to see someone else’s mess (and someone else’s mistakes) than our own, begin there. Ever had a sloppy sibling, roommate, or partner? It’s like that.

You know how aerial/drone photos are all the rage? Their popularity provides a good metaphor: the long range of such images gives a fuller sense of climate catastrophes, such as…

- Unprecedented worldwide flooding. The October 2020 United Nations (UN) report on weather disasters over the prior 20 years directly ties these emergencies to accelerated global warming: “...floods account(ing) for more than 40 per cent of disasters—affecting 1.65 billion people—storms 28 per cent, earthquakes (eight per cent), and extreme temperatures (six per cent).

- The immensity of bushfires ravaging Australia and the western United States.

- 2020’s record-setting number—and intensity—of hurricanes along the eastern US. (Records that began in 1851.)

- Carbon sinks—nature’s way of cleaning up after us—becoming clogged. If we keep destroying forests, one of the best carbon-capturers, we all may wind up sinking.

2020 brought the worst flooding China has seen in 30 years. This aerial photo—courtesy of Getty Images—shows the devastation caused by a breached dam in Jiujiang, central China.

A kangaroo flees the ever-spreading bushfires in Lake Conjola, Australia, 12.31.19. This iconic photo, taken by award-winning photographer Matthew Abbott, was shot midday. Image courtesy of Matthew Abbott.

Other Key Markers of the Anthropocene

Nuclear bombs, fracking, and the biggest: burning fossil fuels.

Key Results

Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the air—the main driver of global warming—are spiking ever higher. Today, carbon dioxide levels are "higher than at any point in at least the past 800,000 years..." and climbing fast. Additionally, as the world's ice sheets begin to melt, sea levels are now on an inexorable rise upwards: a slow, determined and all-encompassing giant.

Storms, floods, and fires. ⇢ Waters rise, glaciers collapse. ⇢ Animals go extinct.

The latest it’s-all-about-us crisis of the past century is, of course, COVID-19. It took a deadly rampage of humanity to awaken us to the deadly response of a destablilzed Earth. So be it. At least we’re woke.

You Need the Earth

This planet doesn’t need us. It got along quite well without us for billions of years. Now that we are here, we must not only acknowledge the hellfire we have wrought upon our home, but do our very best to fix it.

And if you’re going to fix a problem, the first thing to do is name it. The Anthropocene is a literal naming of the problem: us. With such clear and damning evidence, switching to an appropriate name for this epic epoch should be a no brainer—a fast and easy first step before rolling up our sleeves and rolling out repairs, right?

Nope. Only geologists—or those familiar with that world—know that the naming process is never fast. In fact, comparatively speaking, this one is moving quickly. Too quickly for some.

Furthermore, mostly fossil-fuelers—or those familiar with that world—know that their planet-raping endeavors are best assured if we all do not pay attention (but do continue paying them).

You’ll meet the good guys—the scientists—shortly. They move slowly, steadily, scientifically. The heroes are Dutch atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and—IMHO—British geologist Jan Zalasiewicz. But let’s begin with the bad guys.

Your soundtrack starts here: The Devil Put the Coal in the Ground, by Steve Earle.

Fossil Fuelers: Deny, Deceive, Distract, And Drill

“Major fossil fuel companies have known for decades that their products—oil, natural gas, and coal—cause global warming. Their own scientists told them so more than 30 years ago.”

“They knew about global warming… and did worse than nothing… they deceive(d) shareholders, politicians, and the public… about the facts and risks of global warming.”

—Union of Concerned Scientists, June 20, 2019

The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) keeps a Climate Accountability Scorecard, ranking eight of the leading investor-owned fossil fuel companies on four broad areas: disinformation, business planning, policies, and disclosure. The ratings are: advanced, good, fair, poor, and egregious. Lots more info is on their site, but just check out the 2018 ratings for disinformation:

In a 2019 article from “The Guardian,” titled Revealed: the 20 firms behind a third of all carbon emissions, the authors rely on analysis from the Climate Accountability Institute (CAI), which they call “the world’s leading authority on big oil’s role in the escalating climate emergency.” The CAI’s Richard Heede assembled both investor-owned firms (such as Chevron) as well as state-owned companies, the biggest being Saudi Aramco.

Here are the four worst polluters from 1965 to 2017:

- State-owned Saudi Aramco, with nearly 60 billion tons of CO2 emissions in total.

- Chevron, with almost 45 billion tons.

- State-owned Gazprom—Russia’s largest moneymaker—pretty much tied with Chevron.

- ExxonMobil, with nearly 42 billion tons.

And what about f##ckers? That’s frackers, btw, although the top hit in my DuckDuckGo search displayed an... interesting... adjectival form (one I have learned scifi fans will recognize):

Fracking, a “nickname” for hydraulic fracturing, is when chemicals and water are injected into bedrock at mad-high pressure to crack the rocks and extract whatever gas or crude oil is there. Kinda like blasting into a vault and grabbing the gems. But, with a gasmask on, as one of the main pollutants released by fracking is methane—about 13 million metric tons a year—within the US alone. As stated in a 2019 Investopedia article, “Methane is a major greenhouse gas. Its global warming potential is 84 times that of carbon dioxide on a 20-year horizon, and 25 times on a 100-year horizon.”

A 2020 article in Bloomberg Business tags the US company Halliburton as being the world’s biggest fracker. (About 70 percent of oil and gas extracted in the states is done by fracking.)

An Oily Link

Geologist and Professor Jan Zalasiewicz said that there has always been a strong link between geologists and the oil industry, and that a lot of research has also been funded by oil: “It’s useful to find out about rocks if you want to find oil in them.”

When asked about Anthropocene—a name that might be used to blame frackers or anyone in the oil industry—Zalasiewicz points more to geologists, for whom an epoch lasting only 70 years can be a radical notion, especially an epoch including things such as, “... plastics and concrete as characteristic ingredients; that is quite a change for people who have been brought up in traditional geological mode.”

But circling back to big oil and its slippery ilk, Zalasiewicz says their aid “...used to be called ‘The Light Side.’ Now for many incoming geology students —‘who are much more wary of the oil companies than my generation was’—it’s ‘The Dark Side.’”

Further, Zalasiewicz adds this meaningful caveat on foreseeable pushback from entities that would be held accountable: “The Anthropocene clearly is describing the trajectory that Extinction Rebellion and others, Greta Thunberg, say very clearly: this is a very dangerous road for humans… the rise in CO2, the decline in species; all of these things are part of the description of the Anthropocene. And it’s an ongoing, rapidly moving trajectory.”

Your next song: Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology), by Marvin Gaye.

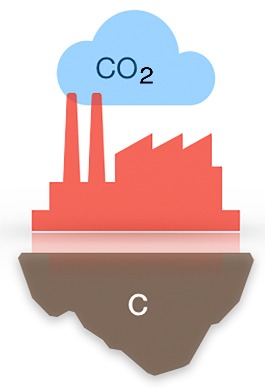

Let’s go back to the importance of carbon (in the ground) and carbon dioxide (in the air). ‘Cause it can be confusing.

Confusing C Words

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)...

Up in the Air

Carbon (C)...

Down in the Ground

Picture carbon curled up underground, fast asleep in fossils and rocks.

Zzzzzz. Snore. Zzzzzz.

It is then violently awoken and dragged up to become fuel. Released into the atmosphere, carbon (C) combines with oxygen (O2) to become carbon dioxide (CO2). “Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas: a gas that absorbs and radiates heat,” reports the US government agency NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

NOAA continues, “Unlike oxygen or nitrogen (which make up most of our atmosphere), greenhouse gases absorb that heat and release it gradually over time, like bricks in a fireplace after the fire goes out.” Those bricks are heating our sky.

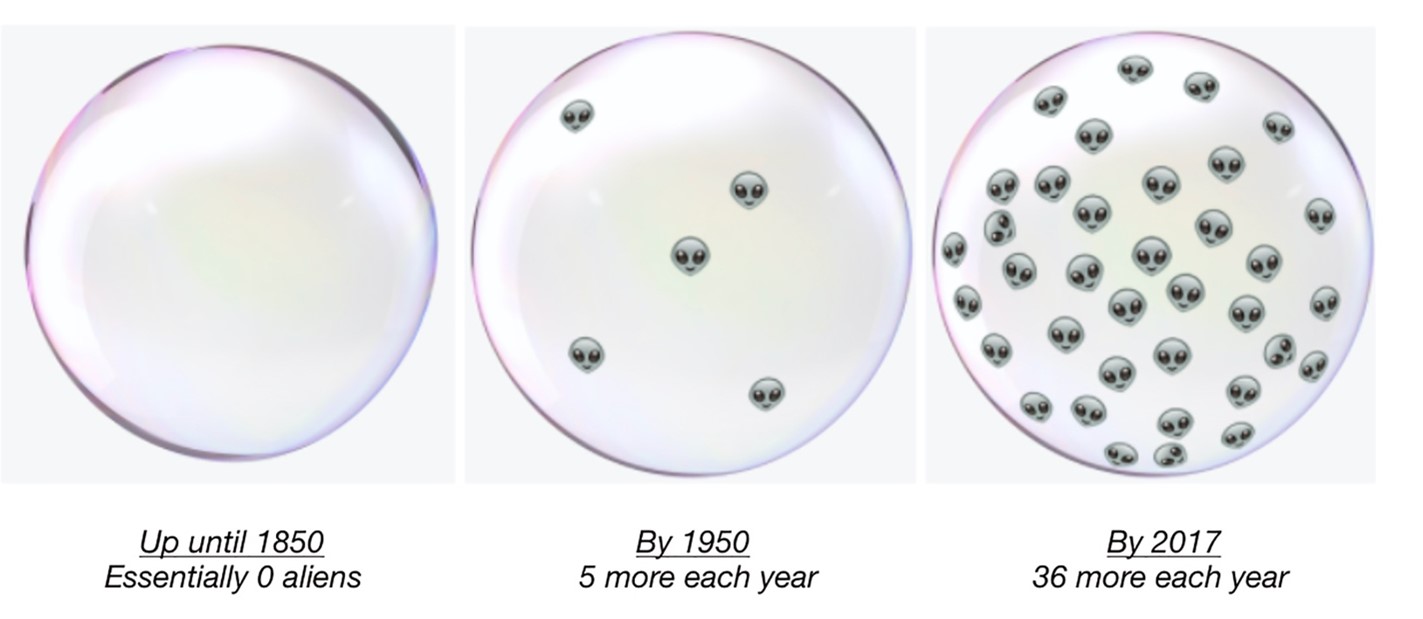

For a visual, try this: aliens in a bubble. Each alien weighs a gigaton of carbon dioxide.

Q: Hold the phone. A gigaton? What on earth is a gigaton?

A: A gigaton is a billion tons. And it’s more, like, over the earth.

Q: Back up. What is a ton? I mean, what does a ton look like?

A: Picture a 1979 Volkswagen Beetle. It’s a ton (around 2,200 pounds/1,000 kilograms).

Now, back to wrapping our minds around a gigaton, both in size and weight. NASA offers this chilling reference. Central Park in New York City is about 2½ miles long and half a mile wide (4 kilometers by 0.8 kilometers). Imagine the entire park covered in a sheet of ice.

Next, that ice is thickened, making it rise a good 1,120 feet high (over 340 meters). That’s higher than the Eiffel Tower in Paris, higher than the tallest building in the entire Southern Hemisphere—the Sky Tower in Auckland, New Zealand. And, don’t forget about the whole width and length thing. That crazy-big ice cube weighs a gigaton.

Enter, aliens, hovering heavily in our atmosphere, each weighing a gigaton:

Of course, our troubles have nothing to do with aliens, and everything to do with us—what we do, and how we try to spin what we do.

The Anthropocene Debate: The Good (if Often Slow) Guys

At first, there was a burst. The light-bulb moment occurred in Mexico, during a February 2000 forum about our planet. Then and there, the name Anthropocene was created by Dutch Nobel-prize winning atmospheric chemist and meteorologist Paul Crutzen (1933 - 2021).

Sadly, Crutzen died during the time I was writing this article. Happily, a good 20 years before his death, during that conference in Mexico, he got ticked off. The results were most excellent.

Listening to a presentation, Crutzen grew increasingly angry at the repeated use of “Holocene.” He stood up and stopped the meeting. Heads swiveled; jaws dropped. His words:

"I suddenly thought this was wrong. The world has changed too much. So I said: ‘No, we are in the Anthropocene.' I just made up the word on the spur of the moment. Everyone was shocked. But it seems to have stuck.”

It sure did. The Earth System science community—those less focused on the past and more on the present—found it extremely useful. It linked all kinds of changes: in the climate, atmosphere, glaciers, ocean currents, biology, and evolution.

A key advocate for dropping Holocene and switching to Anthropocene was American chemist Will Steffen, then executive director of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP). Steffen encouraged Crutzen to write an article about it, which Steffen would (and did) publish in the IGBP newsletter of May 2002.

Across the Pond and in a Lake

As Crutzen further plumbed the depths of the word Anthropocene, he discovered that American lake ecologist Eugene Stoermer (1934 - 2012) had used the word before, in the late 1980s, both with students and peers. (Makes sense: it is an intuitive term.) Crutzen, determined to give Stoermer his fair share of the credit, asked if he wanted to co-write the IGBP article. Stoermer, described as a “laid-back scientist,” did co-author the piece, but didn’t pursue the word’s recognition any further.

Crutzen did, though. Big time. And for those within the geoscience sphere, Crutzen is the man. In 2002, he penned a piece for one of the oldest and most respected journals in science: Nature: “Geology of Mankind.”

A Nobel-prize winner for his work on the ozone layer (he helped discover how the ozone hole was forming), by 2002 he was the most cited author in his field... in the whole world. And mind you, being a scientist, Crutzen wasn’t merely pitching the name Anthropocene; he was developing and monitoring the science behind it, paying close attention as sites around the world were tested and measured for comparable results.

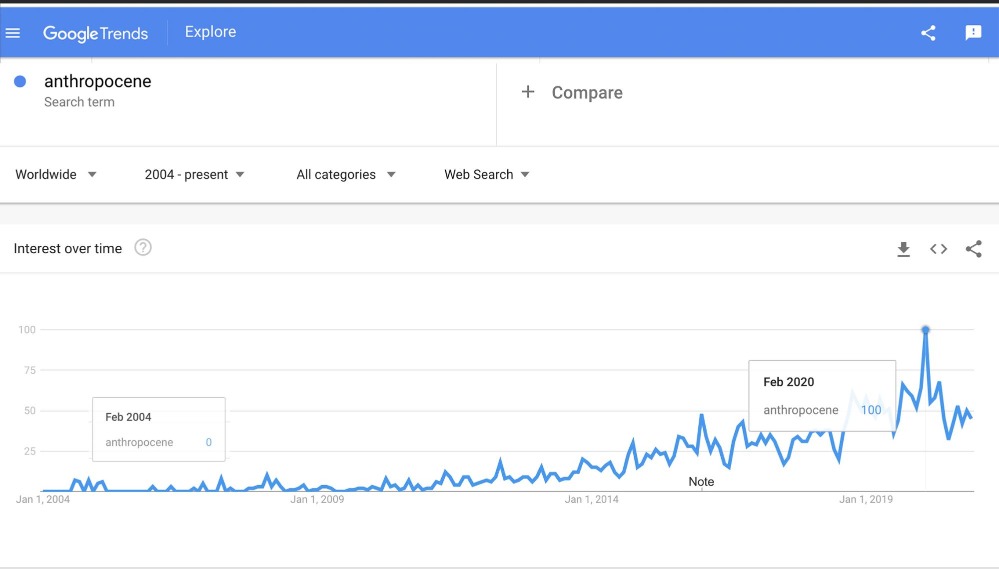

Plus, Anthropocene makes so much sense—imagine: a name that is descriptive and useful. Accordingly, its popularity skyrocketed. Some eye-opening proof of its growing usage? Entering “anthropocene” into Google Trends, we see that in February 2004 it had no worldwide action; February 2020 marked the height of its traction.

The spike at 100 represents the maximum search interest for anthropocene. (That’s close to ten million hits. [Two years earlier, at the start of 2018, the count was ”only” two million.])

Clearly, the word struck a chord, and stuck. But it also got stuck. Why? Within the multi-tiered official scientific ecosystem of commissions and subcommissions, geologists identify each slice of time. And chronologic dating? It is as essential as it is complicated.

Dating

Not only complicated, but unprecedented. Never before has a new time slice been assigned to modernity. At the start of the last “new” one, 12,000 years ago (ya), writing hadn’t been invented (~7,000 ya). Nor were shoes (~ 5,500 ya). Not even the wheel (~5,000 ya). But art? Yes! (~ 45,000 ya.)

And, while the earliest attempts to define and name the tiers of time go back a ways—the nomenclatural system of today began in the late 1700s—that ain’t exactly yesterday. Just to put things in perspective, bicycles weren’t around yet.

Over the next few decades—into the early 1800s and onward—fossil evidence was used to define the different levels. British geologists took the lead—it was the 19th century, after all—and from around 1840 on, they pretty much set everything in, ahem, stone. Then, in 1913, just before World War I, the very first time scale with fixed dates appeared.

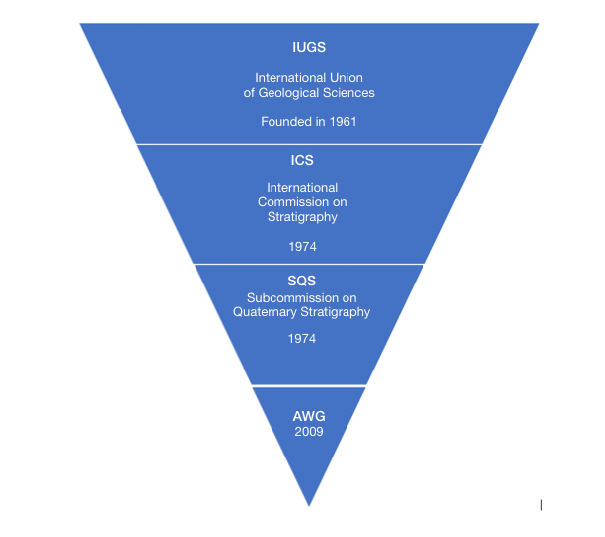

Skip ahead 60 years to 1974, when the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) was formed. The ICS are the researchers; they date all those periods and such, producing charts for every site tested. The sites are called GSSPs (Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points). Each GSSP (aka “golden spike”) defines the lowest level—age and depthwise—for a geologic boundary. Kinda like a birth certificate, but for a rock (and much harder to certify).

GSSPs are examined worldwide. It’s a ton of work (pun-intended), but the experts are optimistic.

So much for dating. Now for naming. Because while the ICS does all the heavy lifting (and digging), the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) are the true deciders. And as you now know, the name Anthropocene is a problem.

Naming

AWG, at the tip of the upside-down triangle, stands for Anthropocene Working Group. They and those listed above meet every four years for the International Geological Congress (IGC). The first IGC took place in 1878, in France, thereafter convening every four years. (Due to COVID-19, the 2020 meeting was postponed until August 2021.)

Remember Paul Crutzen’s “Eureka!” moment in 2000? Here’s what went down eight years later:

In 2008, the aforementioned British geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, then-chair of the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London, proposed to the international community that the Anthropocene Epoch be used as a formal geological interval. The paper he and his colleagues wrote led to the creation of the AWG one year later, with Zalasiewicz as chair.

As Zalasiewicz put it, the key questions were, “Is the Anthropocene real geologically? Does it make sense? Should it be formalized? Can it be formalized on the time scale?” It took several years for Zalasiewicz et al to accept and agree that the evidence—“physical, chemical, and biological… (showing) the dividing lines of history”—was sound. “The Anthropocene matters,” he said. “We have something real on our hands, and we should try and do something about it.”

Jan Zalasiewicz: The Unstoppable Engine Keeping the “A” Train Going

Zalasiewicz, a veritable force of nature when it comes to pushing the acceptance of Anthropocene, is also relentlessly modest. In the interview for this article, he gave all credit to Crutzen, as well as the 30+ people in the AWG. Zalasiewicz has co-authored and solely authored both scholarly articles on the Anthropocene as well as those for the public at large.

Said approach—reaching out to both audiences—is key, though writing for the general public is pretty much terra nova for geology. Geology is decidedly not in the fancy, shiny spotlight of science, which is an important point. Why? Money from funding councils—and attention from anyone—is often lacking. And don’t forget: big money can spend big money to cover its ass… ets. Yeah. Assets. Over two billion in US dollars.

Cruisin’ the Fossil Coastline Artwork © Ray Troll, 2017

As for speed from within the geologic world, that’s not a thing. The GSSPs described earlier? Many established time units still don’t have one, including the Cretaceous Period (spanning 145 million to 66 million years ago). And it is now 200 years after it was recognized as a unit! The more recent and thus easier to research Holocene—which began 12 thousand years ago—only gained its GSSP in 2008. Crikey!

So, no spotlight on geology, maybe, but people and politics in it? Oh, yeah. Says Zalasiewicz, “There can be a lot of politics involved. Stratigraphers can get very heated about their particular favorites and interpretations. And like a lot of science, it’s very difficult to hurry.”

Regarding the Anthropocene, he adds, “For most time units, most people don’t care, except stratigraphers… with the Anthropocene, people do care… and so, we have felt a bit of pressure.” Acknowledging that vibe, in 2015 the AWG took action, suggesting that the Anthropocene might be formalized using a short-cut in the procedure, by simply choosing a time boundary (a ‘GSSA,’ or Global Standard Stratigraphic Age [technically, it’s allowed by the rulebooks]) — rather than going through the long, expensive, and complicated process of finding a GSSP ‘golden spike.’

Hear Ye, Hear Ye!

The ICS response?

Zalasiewicz: “... they hated that.”

The AWG took note. Timed for the 2016 quadrennial IGC meeting—where the results would be announced—the AWG held a virtual (online) vote, and AWG’s members overwhelmingly recommended the Anthropocene as a formal geologic epoch – and to do so via a ‘golden spike.’

Furthermore, due to the aforementioned ICS 2020 summit postponement, Zalasiewicz reckons they won’t decide on the Anthropocene until 2024. The forestalled formalization notwithstanding, in late 2020, the ICS itself gave Zalasiewicz a leg up, as he became chair of the Quaternary Subcommission.

As of December 2020, still quite new to the group, Zalasiewicz was not at all sure how the many voting members felt about sealing the deal on Anthropocene. “We need more than 60% acceptance at each level for it to go through… It’s a big ask.” Patient and understanding, he’s also tenacious and determined. “The main thing we’re trying to do is to demonstrate the reality of the phenomenon.”

And as any XR rebel can tell you…

...A Great Way to Demonstrate Reality is to Do So Theatrically!

No surprise there: XR is famous for garnering worldwide attention using glorious garb and stunning scenes within peaceful protests. Another group focused on global arts, science, and politics, has not only been on the stage with theatrical productions, it has also been at the bank. The Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW—House of the World’s Cultures), based in Berlin, Germany—are phenomenal fundraisers. And for years—since 2014—HKW has focused on the Anthropocene.

“In the Anthropocene, geological and human history are deeply interwoven, making it difficult to maintain categories like nature and culture.” In 2018, the HKW acquired “serious funding” (Zalasiewicz’s words) from the German government for the AWG to test all those GSSP sites: €800,000. (In US dollars, 800,000 euros is roughly one million bucks.)

Zalasiewicz estimates it’ll be sometime in 2022 at the very earliest for all the testing to be done, all the analyses assembled. The AWG should then, by the 2024 IUGS meeting, have all its ducks in a row. Leading the AWG now, and guiding this process, are Colin Waters as Chair and Simon Turner as Secretary.

Only then, at the tail end of a very long interview, does Zalasiewicz reveal that he and two colleagues—paleobiologist Mark Williams and historian / humanist Julia Adeney Thomas—had just written and published a book, “The Anthropocene: A Multidisciplinary Approach.” No doubt the forthcoming reviews will help sound the alarm. (Prepare yourselves, librarians. ; - )

Power to The People

The reins of power are rarely willingly released. Therefore, we must not be complacent. In the United States, after 400 years of disregarding and disrespecting the history and continuing injustice of enslaved Africans and the generations that followed, the world is watching. The Black Lives Matter movement cannot be ignored. It has, at long last, gone global.

The first step? Naming the movement. Accurately. The next? Moving forward.

Jacob at a Black Lives Matter event in Greenwich Village, New York City, holding a sign he shouldn’t have to. Photo: author.

Sister Shirley making the Black Power symbol at an XR event in lower Manhattan. Photo: author.

Go Make a Scene in the Anthropocene!

So, while we are here—you, reading this text right now—let’s do what we can to right the wrongs, rethink old beliefs and actions, and make Earth the best place it can be. For us, for kangaroos and katydids, for ferns and fruit, and for the future.

Photo: author.

And let us do so peacefully. No breaking into buildings, no catastrophic chaos.

Drama? Sure. Trauma? Nope.

Your last song: Anthropocene by Samsa (naughty version) (”clean” one).

Enjoy!